To mark the closing of Slam City Skates’ Covent Garden shop today after 27 years, we decided to publish Will Harmon’s retrospective article about Slam from our 2012 collaboration with Nike SB, The Edition. The article was written and researched in late 2011, Slam’s 25th year in business. Words: Will Harmon Scans: Paul Gonella  Photo: Sam Ashley In the Beginning Paul Sunman started Slam City Skates through the west London record shop Rough Trade in 1986. Before there were skateboards, Rough Trade used to sell issues of Thrasher behind the counter – there was an important link between punk rock and skateboarding at that time. One day, in the mid ’80s, a big Alpine Sports shop closed down, one of the only places in London you could buy skateboards back then. Soon after, in 1986, skateboarder Paul Sunman decided to fill that gap and start selling skateboards. “Paul had a lot of vision,” said Russell Waterman, Slam employee from 1988-98. “He opened a skate shop at a time when skateboarding was considered a kid’s fad, already in the past. No one realised that all this stuff was going on over in the US, this was pre-internet.” Before Slam City Skates opened on Talbot Road, west London in ’86, it was difficult to get quality skateboards and accessories in London. Slam carried all the latest brands from the US, such as Powell Peralta, Vision, Santa Cruz and Alva. As time went on and skateboarding in Britain began to increase in popularity, Slam expanded and moved downstairs to take over the basement of Rough Trade. Andy Hartwell, Slam employee in the mid ’90s, described his first visit to Slam on Talbot Road: “The first time I went, there was a little kid in there and he asked the guy behind the counter: ‘How high can you ollie?’ The employee replied: ‘How long’s a piece of string?’” Slam’s customer service around this time was notorious and similar to that which you might expect from an independent record shop. In fact, it has been commonly rumoured that the record shop in Nick Hornby’s novel High Fidelity (adapted into a film starring John Cusack) was based on Rough Trade, the record shop that housed Slam. Slam remained on Talbot Road for a couple of years, until the owners decided to open a new shop in Covent Garden, central London in 1988. The new premises in Neal’s Yard housed both skate and record shops, however this time the layout was switched; Slam was upstairs and Rough Trade was down the spiral staircase in the basement.

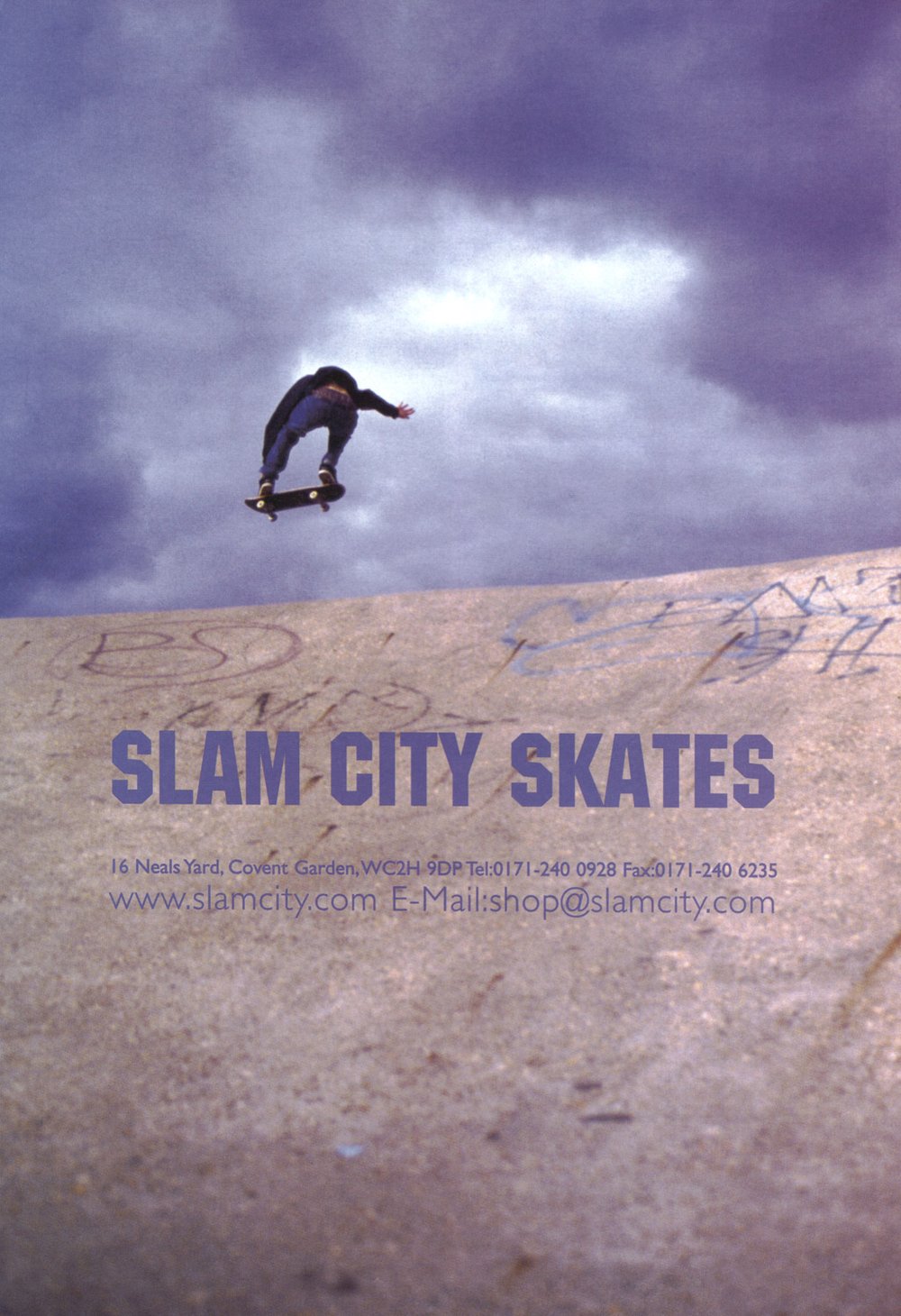

Photo: Sam Ashley In the Beginning Paul Sunman started Slam City Skates through the west London record shop Rough Trade in 1986. Before there were skateboards, Rough Trade used to sell issues of Thrasher behind the counter – there was an important link between punk rock and skateboarding at that time. One day, in the mid ’80s, a big Alpine Sports shop closed down, one of the only places in London you could buy skateboards back then. Soon after, in 1986, skateboarder Paul Sunman decided to fill that gap and start selling skateboards. “Paul had a lot of vision,” said Russell Waterman, Slam employee from 1988-98. “He opened a skate shop at a time when skateboarding was considered a kid’s fad, already in the past. No one realised that all this stuff was going on over in the US, this was pre-internet.” Before Slam City Skates opened on Talbot Road, west London in ’86, it was difficult to get quality skateboards and accessories in London. Slam carried all the latest brands from the US, such as Powell Peralta, Vision, Santa Cruz and Alva. As time went on and skateboarding in Britain began to increase in popularity, Slam expanded and moved downstairs to take over the basement of Rough Trade. Andy Hartwell, Slam employee in the mid ’90s, described his first visit to Slam on Talbot Road: “The first time I went, there was a little kid in there and he asked the guy behind the counter: ‘How high can you ollie?’ The employee replied: ‘How long’s a piece of string?’” Slam’s customer service around this time was notorious and similar to that which you might expect from an independent record shop. In fact, it has been commonly rumoured that the record shop in Nick Hornby’s novel High Fidelity (adapted into a film starring John Cusack) was based on Rough Trade, the record shop that housed Slam. Slam remained on Talbot Road for a couple of years, until the owners decided to open a new shop in Covent Garden, central London in 1988. The new premises in Neal’s Yard housed both skate and record shops, however this time the layout was switched; Slam was upstairs and Rough Trade was down the spiral staircase in the basement.  ‘Extra Special’ advertisement from Sidewalk magazine, 1995. Covent Garden Slam City Skates has been located at 16 Neal’s Yard in Covent Garden since 1988. Through the decades, the area surrounding the shop has changed considerably. What was once a destination for unique independent retailers, selling hard-to-come-by goods, has now become an area predominantly filled with homogenous chain stores and high street brands. Hartwell described the area back in the mid ’90s: “Neal’s Yard was like a crazy hippy enclave. There were loads of vegan cafes, a Chinese medicine shop, a hypnotist, even a crystal shop next door. Neal Street had kite shops and dozens of other independent hippy shops.” “Over the years the landlords have just chipped away at those independent retailers when their lease ends,” said Seth Curtis, Slam employee from 1997-2005. “When a shop signs up for a 10-year lease, they pay rates that reflect the time that they started. For instance, if a shop opens in 1995 and a 10-year lease is signed, the increases throughout that period will be relatively small. But then come 2005, when the lease has ended, the rates could double, sometimes even triple. What independent retailer is going to want to pay that? They can’t stick that out, and who does the landlord call up? They call Quiksilver or O’Neill, or Miss Sixty or whoever. And now Neal Street is just like Carnaby Street, it’s just all these big businesses.” But being one of the few remaining independent shops left in the area is not always such a bad thing, suggested Slam business manager, Chris Pulman: “It’s great for us, because we stick out like a sore thumb as an interesting place to go.”

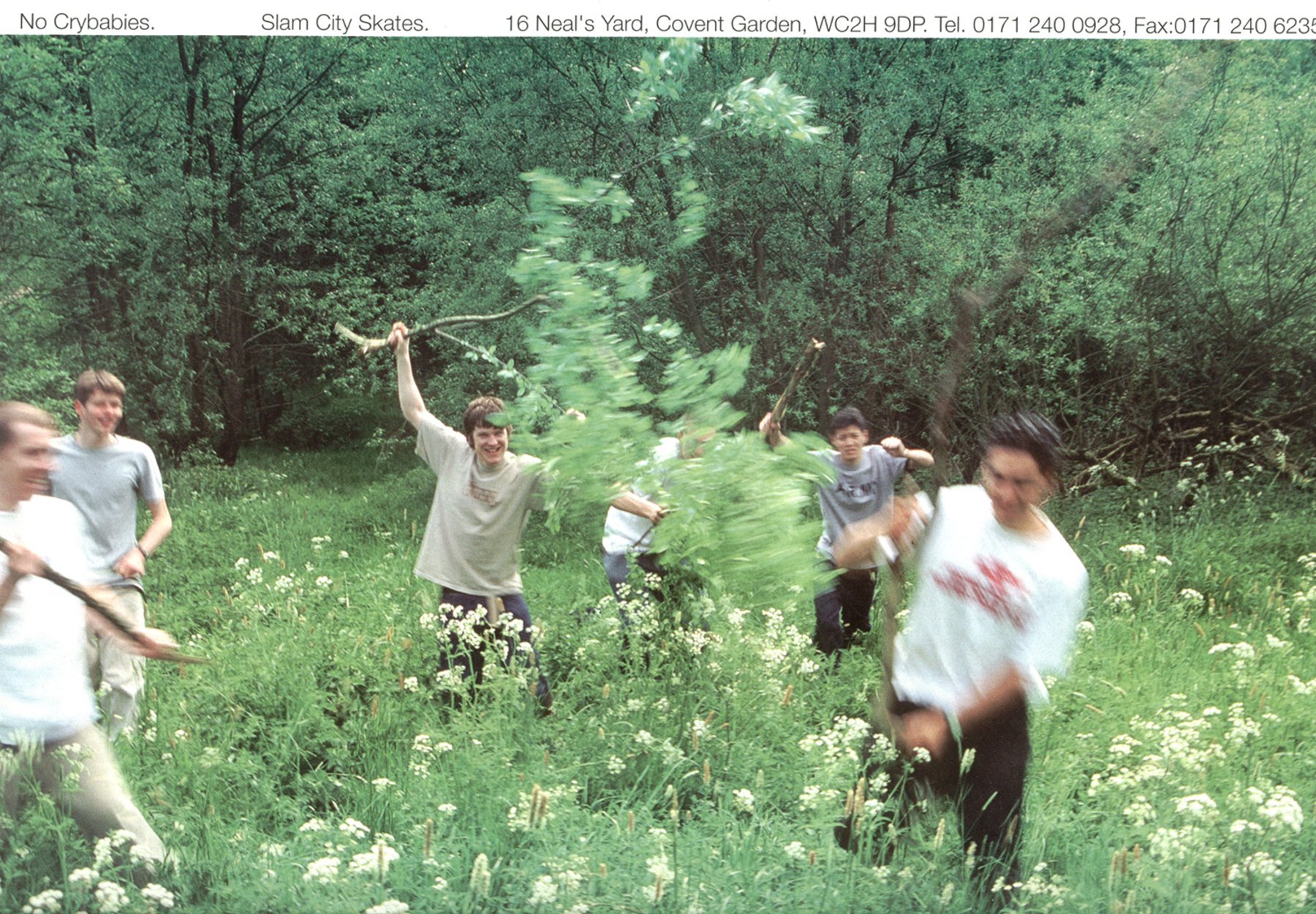

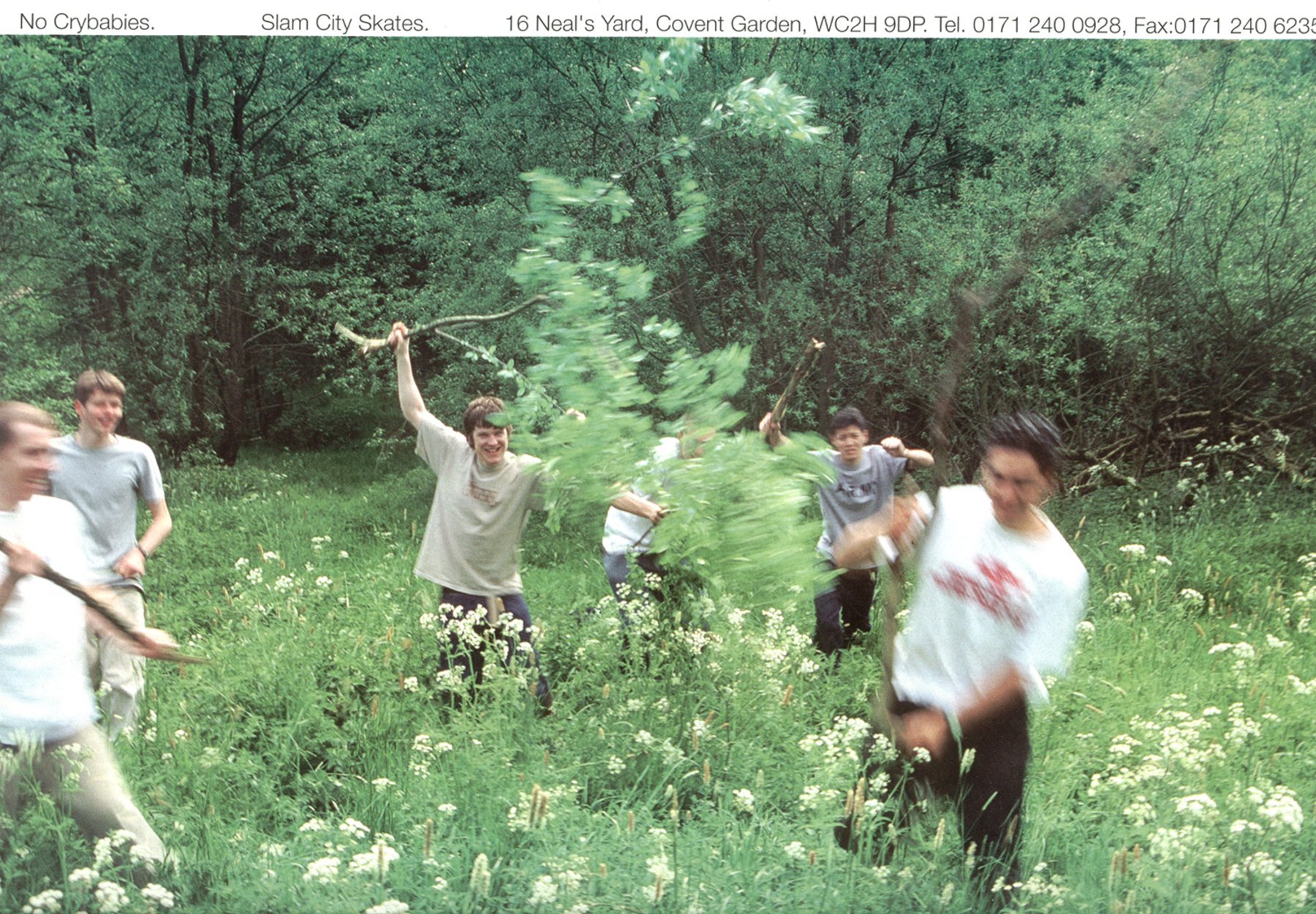

‘Extra Special’ advertisement from Sidewalk magazine, 1995. Covent Garden Slam City Skates has been located at 16 Neal’s Yard in Covent Garden since 1988. Through the decades, the area surrounding the shop has changed considerably. What was once a destination for unique independent retailers, selling hard-to-come-by goods, has now become an area predominantly filled with homogenous chain stores and high street brands. Hartwell described the area back in the mid ’90s: “Neal’s Yard was like a crazy hippy enclave. There were loads of vegan cafes, a Chinese medicine shop, a hypnotist, even a crystal shop next door. Neal Street had kite shops and dozens of other independent hippy shops.” “Over the years the landlords have just chipped away at those independent retailers when their lease ends,” said Seth Curtis, Slam employee from 1997-2005. “When a shop signs up for a 10-year lease, they pay rates that reflect the time that they started. For instance, if a shop opens in 1995 and a 10-year lease is signed, the increases throughout that period will be relatively small. But then come 2005, when the lease has ended, the rates could double, sometimes even triple. What independent retailer is going to want to pay that? They can’t stick that out, and who does the landlord call up? They call Quiksilver or O’Neill, or Miss Sixty or whoever. And now Neal Street is just like Carnaby Street, it’s just all these big businesses.” But being one of the few remaining independent shops left in the area is not always such a bad thing, suggested Slam business manager, Chris Pulman: “It’s great for us, because we stick out like a sore thumb as an interesting place to go.”  ‘No Crybabies’ advertisement from RAD magazine, 1995. Links with Rough Trade For the majority of its 25 years Slam has been intertwined with Rough Trade. But in 2007 Rough Trade moved out of the basement of 16 Neal’s Yard and into a larger, roomier location in east London. According to veteran employee, Jacob Sawyer at least three times a day someone comes into Slam still expecting to find Rough Trade downstairs. Hartwell explained that the combination of a record shop and skate shop came out of a different era, when a lot of shops were more radical in the way they approached retail: “It seems like a very odd mixture, but it worked really well. It came out of that left-wing, slightly punky idea I suppose: ‘Why don’t we combine the two stores?’” The combination of Slam and Rough Trade drew a mixed crowd. Record collectors, artists, music lovers, skateboarders, musicians and of course the ever-present and often aloof tourist made each day working at Slam unique. Ben Sansbury, who worked at Slam in the mid ’90s, recalled a particularly memorable encounter: “Once I was talking to this American about skating. I had no idea who he was, but he said he knew Jason Lee. Then I watched him go downstairs and start playing music and I realised it was Thurston Moore from Sonic Youth.” One of the perks of working above Rough Trade was being able to witness all the in-store live gigs. “Some of my favourites were Steve Shelley and Thurston Moore, also Jeff Buckley,” said Hartwell. “The Beastie Boys gig was a really big one. Everybody wanted to go to that one.” Often people who were playing downstairs would come up and buy T-shirts and other items from Slam: “The guys from Coil used to come in quite a lot, so I met them and they would buy shirts and stuff,” recalled Hartwell. Sawyer’s favourite Rough Trade related transactions involved The Black Lips, who bought Slam shirts, and Jason Molina of Magnolia Electric Co., who wanted skate stickers for his guitar. When Rough Trade moved out of Covent Garden, a lot of Slam employees experienced a feeling of disconnection with the current music scene. “I seriously miss working above Rough Trade; hearing fresh, up to date music every single week,” said Pulman. Another perk he misses was getting on the guest list for the best gigs in town. “Working above Rough Trade was great,” said Curtis. “The staff were just hilarious. They were these ageing hippies with insane music knowledge, Neil (McKay) and Jamie especially. I would challenge anyone on Jamie Tugwell’s knowledge of global music.” Pulman saw a downside to working in the basement however, describing the “nocturnal demeanour” of his subterranean colleagues. But when it came to music knowledge, he agreed with Curtis: “The guys down there, they really were High Fidelity; they knew their crap!”

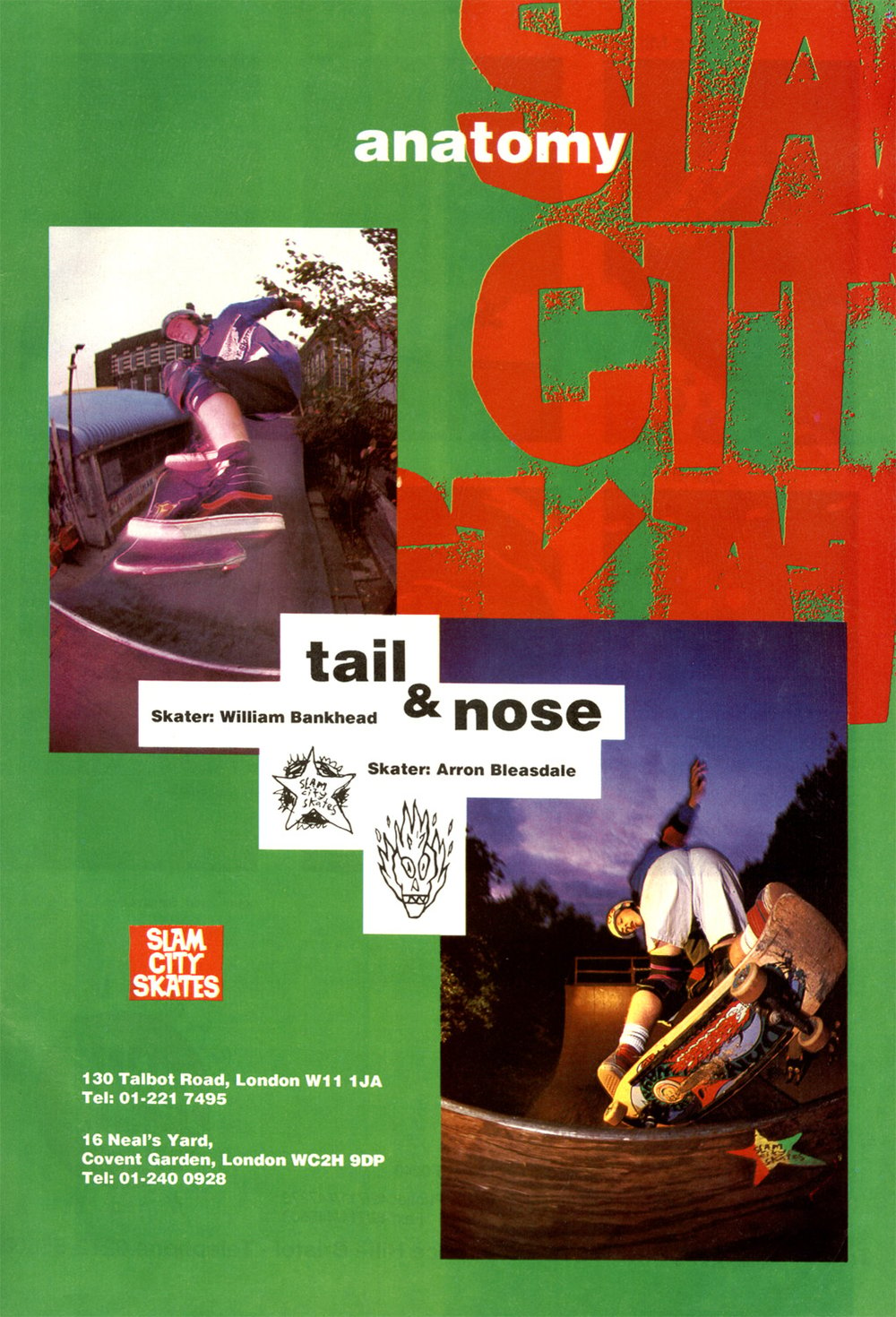

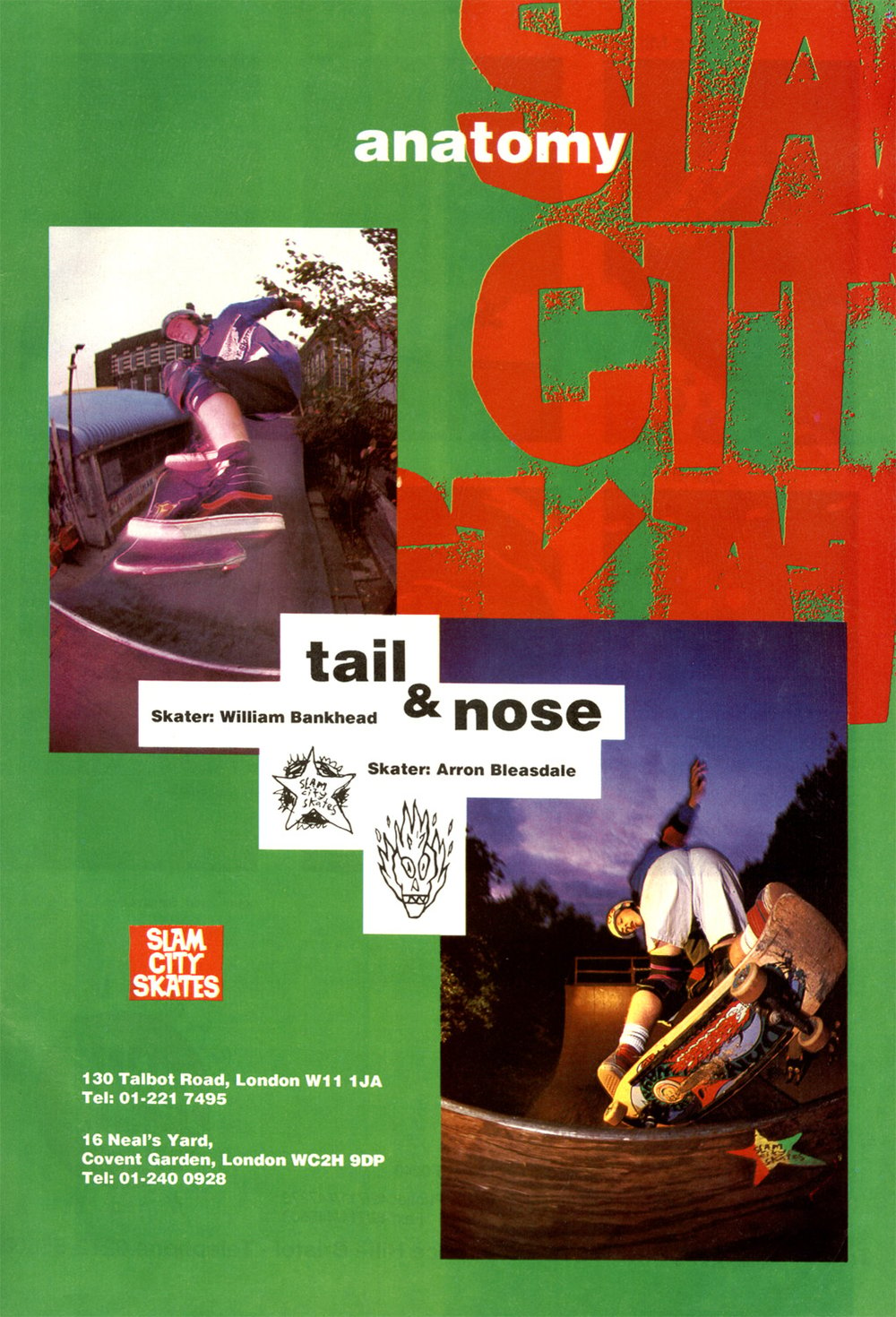

‘No Crybabies’ advertisement from RAD magazine, 1995. Links with Rough Trade For the majority of its 25 years Slam has been intertwined with Rough Trade. But in 2007 Rough Trade moved out of the basement of 16 Neal’s Yard and into a larger, roomier location in east London. According to veteran employee, Jacob Sawyer at least three times a day someone comes into Slam still expecting to find Rough Trade downstairs. Hartwell explained that the combination of a record shop and skate shop came out of a different era, when a lot of shops were more radical in the way they approached retail: “It seems like a very odd mixture, but it worked really well. It came out of that left-wing, slightly punky idea I suppose: ‘Why don’t we combine the two stores?’” The combination of Slam and Rough Trade drew a mixed crowd. Record collectors, artists, music lovers, skateboarders, musicians and of course the ever-present and often aloof tourist made each day working at Slam unique. Ben Sansbury, who worked at Slam in the mid ’90s, recalled a particularly memorable encounter: “Once I was talking to this American about skating. I had no idea who he was, but he said he knew Jason Lee. Then I watched him go downstairs and start playing music and I realised it was Thurston Moore from Sonic Youth.” One of the perks of working above Rough Trade was being able to witness all the in-store live gigs. “Some of my favourites were Steve Shelley and Thurston Moore, also Jeff Buckley,” said Hartwell. “The Beastie Boys gig was a really big one. Everybody wanted to go to that one.” Often people who were playing downstairs would come up and buy T-shirts and other items from Slam: “The guys from Coil used to come in quite a lot, so I met them and they would buy shirts and stuff,” recalled Hartwell. Sawyer’s favourite Rough Trade related transactions involved The Black Lips, who bought Slam shirts, and Jason Molina of Magnolia Electric Co., who wanted skate stickers for his guitar. When Rough Trade moved out of Covent Garden, a lot of Slam employees experienced a feeling of disconnection with the current music scene. “I seriously miss working above Rough Trade; hearing fresh, up to date music every single week,” said Pulman. Another perk he misses was getting on the guest list for the best gigs in town. “Working above Rough Trade was great,” said Curtis. “The staff were just hilarious. They were these ageing hippies with insane music knowledge, Neil (McKay) and Jamie especially. I would challenge anyone on Jamie Tugwell’s knowledge of global music.” Pulman saw a downside to working in the basement however, describing the “nocturnal demeanour” of his subterranean colleagues. But when it came to music knowledge, he agreed with Curtis: “The guys down there, they really were High Fidelity; they knew their crap!”  ‘Anatomy’ advertisement from RAD magazine, 1990, featuring Will Bankhead and Arron Bleasdale. The University of Slam “Slam was almost like a university for a lot of people,” said Gareth Skewis, Slam co-owner and former employee. Countless Slam alumni have gone on to be successful musicians, pro skaters and artists, with many starting their own companies and artistic projects. One of the most notable is Russell Waterman, who after starting Holmes clothing at Slam, left to create the immensely successful Silas clothing label with Sofia Prantera. Then there was Andy Hartwell, who started his own clothing company Oeuf, as did Toby Shuall with Suburban Bliss. With the help of Slam, former employee Mark ‘Fos’ Foster created the skate company Organic, which eventually became Landscape Skateboards. Pete Hellicar started Unabomber Skateboards while working at the Slam warehouse and former Slam employee Andy Holmes was instrumental in the publication of Dysfunctional, a critically acclaimed book about the history of skateboarding, published in 1999. Will Bankhead described his era working at the shop in the early ’90s: “Everyone was involved and we would all share the experience.” According to Bankhead, the staff would watch the latest videos, read the new magazines and check out all the latest board graphics. And everyone would have input when it came to Slam’s creative endeavours: “With the record shop downstairs, we learned so much about music and graphics and Paul (Sunman) would really pull it all together and get people to work on the ads and stuff.” Bankhead later went on to design graphics for Mo’ Wax records. Another example of a successful alumnus is Gareth Skewis, who used his experience and connections gained from working at Slam to get a job at Silas in 2000. Then, in 2004, he left Silas to run Pointer footwear. In 2007, Skewis returned to his old work place and, with the help of a couple of partners, bought Slam from Rough Trade. According to Skewis, Slam has always had a history of taking risks, regardless of who the owners were: “It’s always had a real creative hub of people around it. That’s because of where it is and because it’s not a corporate constructed environment – it’s more like a 16 year-old art student’s bedroom.”

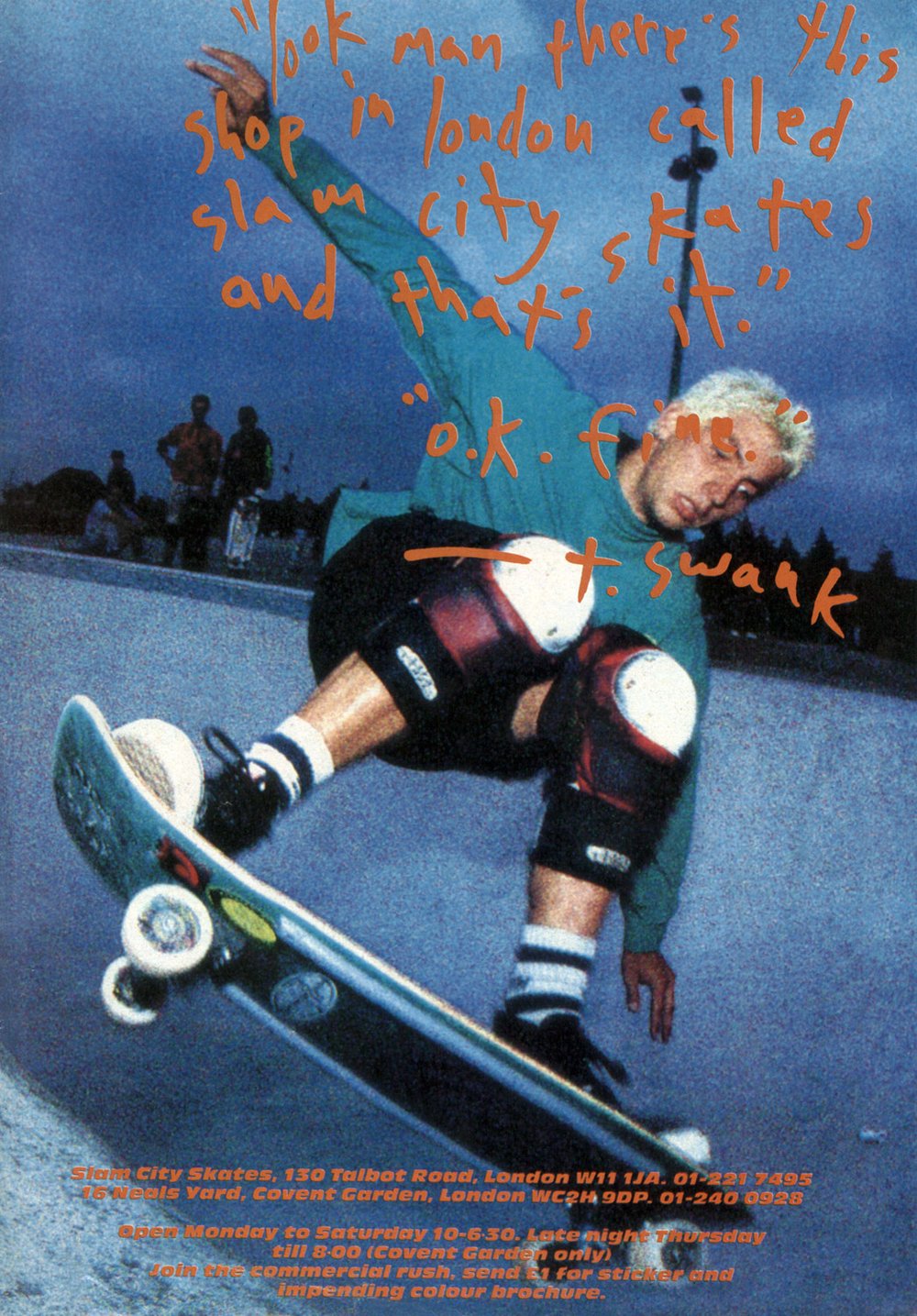

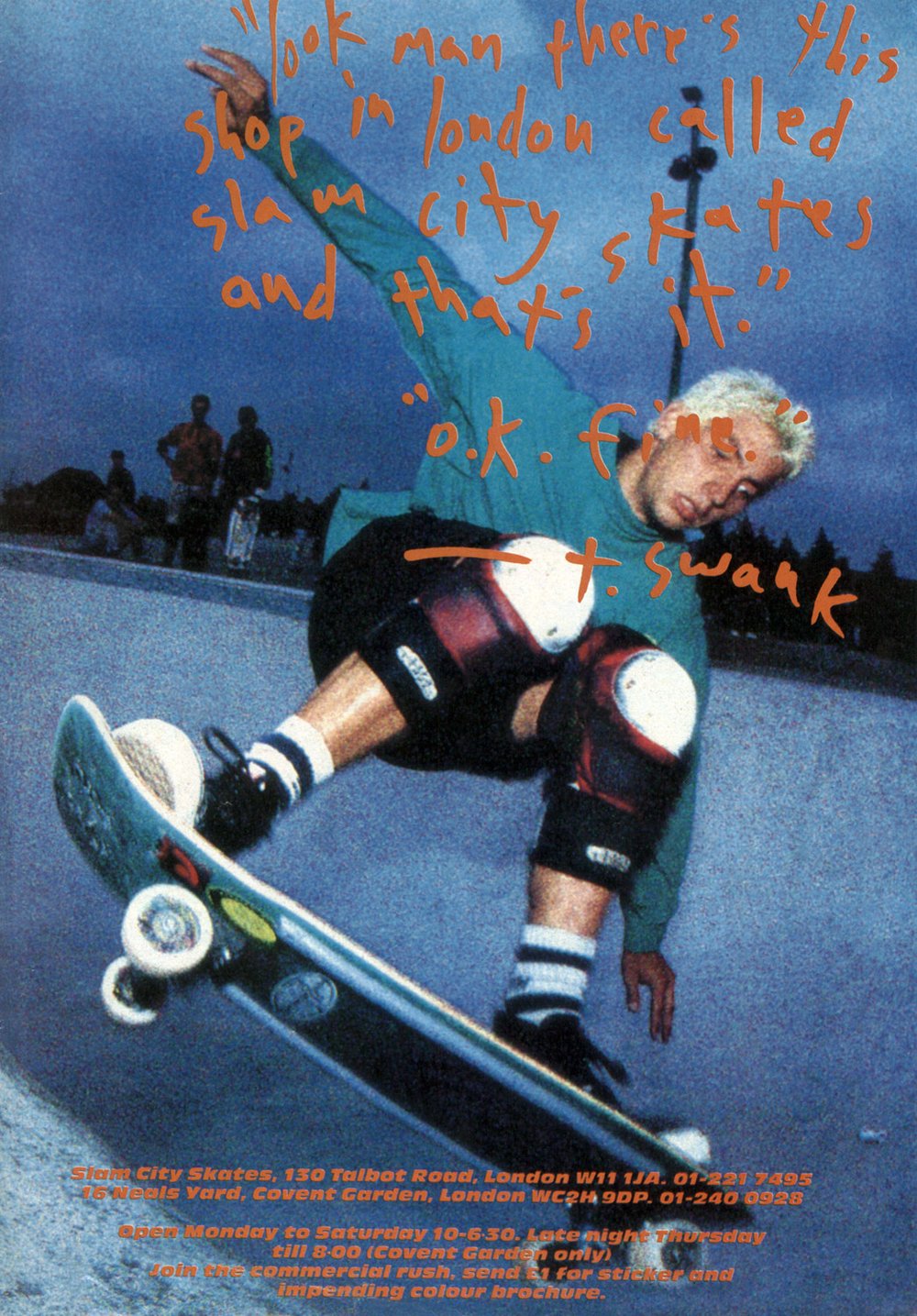

‘Anatomy’ advertisement from RAD magazine, 1990, featuring Will Bankhead and Arron Bleasdale. The University of Slam “Slam was almost like a university for a lot of people,” said Gareth Skewis, Slam co-owner and former employee. Countless Slam alumni have gone on to be successful musicians, pro skaters and artists, with many starting their own companies and artistic projects. One of the most notable is Russell Waterman, who after starting Holmes clothing at Slam, left to create the immensely successful Silas clothing label with Sofia Prantera. Then there was Andy Hartwell, who started his own clothing company Oeuf, as did Toby Shuall with Suburban Bliss. With the help of Slam, former employee Mark ‘Fos’ Foster created the skate company Organic, which eventually became Landscape Skateboards. Pete Hellicar started Unabomber Skateboards while working at the Slam warehouse and former Slam employee Andy Holmes was instrumental in the publication of Dysfunctional, a critically acclaimed book about the history of skateboarding, published in 1999. Will Bankhead described his era working at the shop in the early ’90s: “Everyone was involved and we would all share the experience.” According to Bankhead, the staff would watch the latest videos, read the new magazines and check out all the latest board graphics. And everyone would have input when it came to Slam’s creative endeavours: “With the record shop downstairs, we learned so much about music and graphics and Paul (Sunman) would really pull it all together and get people to work on the ads and stuff.” Bankhead later went on to design graphics for Mo’ Wax records. Another example of a successful alumnus is Gareth Skewis, who used his experience and connections gained from working at Slam to get a job at Silas in 2000. Then, in 2004, he left Silas to run Pointer footwear. In 2007, Skewis returned to his old work place and, with the help of a couple of partners, bought Slam from Rough Trade. According to Skewis, Slam has always had a history of taking risks, regardless of who the owners were: “It’s always had a real creative hub of people around it. That’s because of where it is and because it’s not a corporate constructed environment – it’s more like a 16 year-old art student’s bedroom.”  Advertisement from RAD magazine, 1989, featuring Tod Swank. A Job like No Other “It was one of those jobs where it was more than just a job,” said Hartwell. “Once you got fished in, you were really part of the team, part of a family almost.” Employees would often stay late to rearrange the shop and do stocktakes without being paid overtime. This was because Slam staff felt actively involved and cared about the shop, explained Hartwell: “We actually all gave a shit about what we were doing and that’s something that I’ve not found with a lot of other jobs.” Nik Taylor, who worked at Slam between 1998 and 2000, explained how it really stood out compared to other London skate shops at the time, like Hi-Jinx and Skate of Mind: “These other shops were really centres of commerce, while Slam felt quite hippy-ish.” He described Slam at the time as feeling like the total antithesis of Covent Garden and all the other London skate shops that were “just trying to push business”. More so than other skate shops, Slam was a place to hang out: “We are sitting ducks. You see everyone in here. Slam is a refuge for the bored, jobless and absolutely insane,” said Sawyer. Even employees would spend their days-off lost in the ‘Slam Vortex’. Once entered it was almost impossible to leave: there was always a new video or magazine to check out and of course the obvious “it’s raining outside” excuse. So it’s not surprising that for many of its employees, Slam became the centre of their social world in London. In 1997, at the age of 20, Seth Curtis moved to the city specifically to work at Slam. “You meet so many people passing through; I met so many people that were influential to me,” said Curtis, who even met his wife at Slam when she came in and asked him out. Now they have a three-year-old son. “Slam has always been the centre of my life in London and I wouldn’t be with my wife and now my son if it wasn’t for the shop. That shop… it’s still everything to me.”

Advertisement from RAD magazine, 1989, featuring Tod Swank. A Job like No Other “It was one of those jobs where it was more than just a job,” said Hartwell. “Once you got fished in, you were really part of the team, part of a family almost.” Employees would often stay late to rearrange the shop and do stocktakes without being paid overtime. This was because Slam staff felt actively involved and cared about the shop, explained Hartwell: “We actually all gave a shit about what we were doing and that’s something that I’ve not found with a lot of other jobs.” Nik Taylor, who worked at Slam between 1998 and 2000, explained how it really stood out compared to other London skate shops at the time, like Hi-Jinx and Skate of Mind: “These other shops were really centres of commerce, while Slam felt quite hippy-ish.” He described Slam at the time as feeling like the total antithesis of Covent Garden and all the other London skate shops that were “just trying to push business”. More so than other skate shops, Slam was a place to hang out: “We are sitting ducks. You see everyone in here. Slam is a refuge for the bored, jobless and absolutely insane,” said Sawyer. Even employees would spend their days-off lost in the ‘Slam Vortex’. Once entered it was almost impossible to leave: there was always a new video or magazine to check out and of course the obvious “it’s raining outside” excuse. So it’s not surprising that for many of its employees, Slam became the centre of their social world in London. In 1997, at the age of 20, Seth Curtis moved to the city specifically to work at Slam. “You meet so many people passing through; I met so many people that were influential to me,” said Curtis, who even met his wife at Slam when she came in and asked him out. Now they have a three-year-old son. “Slam has always been the centre of my life in London and I wouldn’t be with my wife and now my son if it wasn’t for the shop. That shop… it’s still everything to me.”  Advertisement from Sidewalk magazine, 1997, featuring Reuben Goodyear. A Home from Home With its relaxed atmosphere and lenient approach to commerce it’s hardly surprising that the staff pushed some boundaries and took some liberties. A lot was tolerated in the early days. One particular phenomenon that illustrates this perfectly, was that of employees sleeping in the shop. This was mostly the result of either a bad hangover or not even making it home from the night before – to many, crashing at the shop was a preferred alternative to the night bus home. “We used to go out to Cheap Skates (student night in Soho) every Wednesday night,” recalled Greg Finch, who worked at Slam between 1999 and 2001. “It was only 60p a drink, and we’d get so hammered that we’d literally be passing out underneath the clothes rails the next day.” Staff would often spend Thursdays sleeping under the T-shirt rail, after showing up to work still drunk. “Because there were so many T-shirts packed into a small space, you could totally get in there, get underneath it and nobody would find you,” said Finch. But not all of the sleeping was booze related. Finch actually slept in the shop for three months while between flats, storing all his stuff behind the board wall and showering at friends’ homes. “I’d get all the jackets and lay them down on the floor and lay a Unabomber sleeping bag on top. I had to make sure I was awake before work started. I’d pack everything up and go out and wait for the first people to come in and then I’d come back in.” Finch got so comfortable there, he actually began inviting people back with him to stay. And when he did finally find a new flat, he got DHL to deliver all his belongings there… on Slam’s bill.

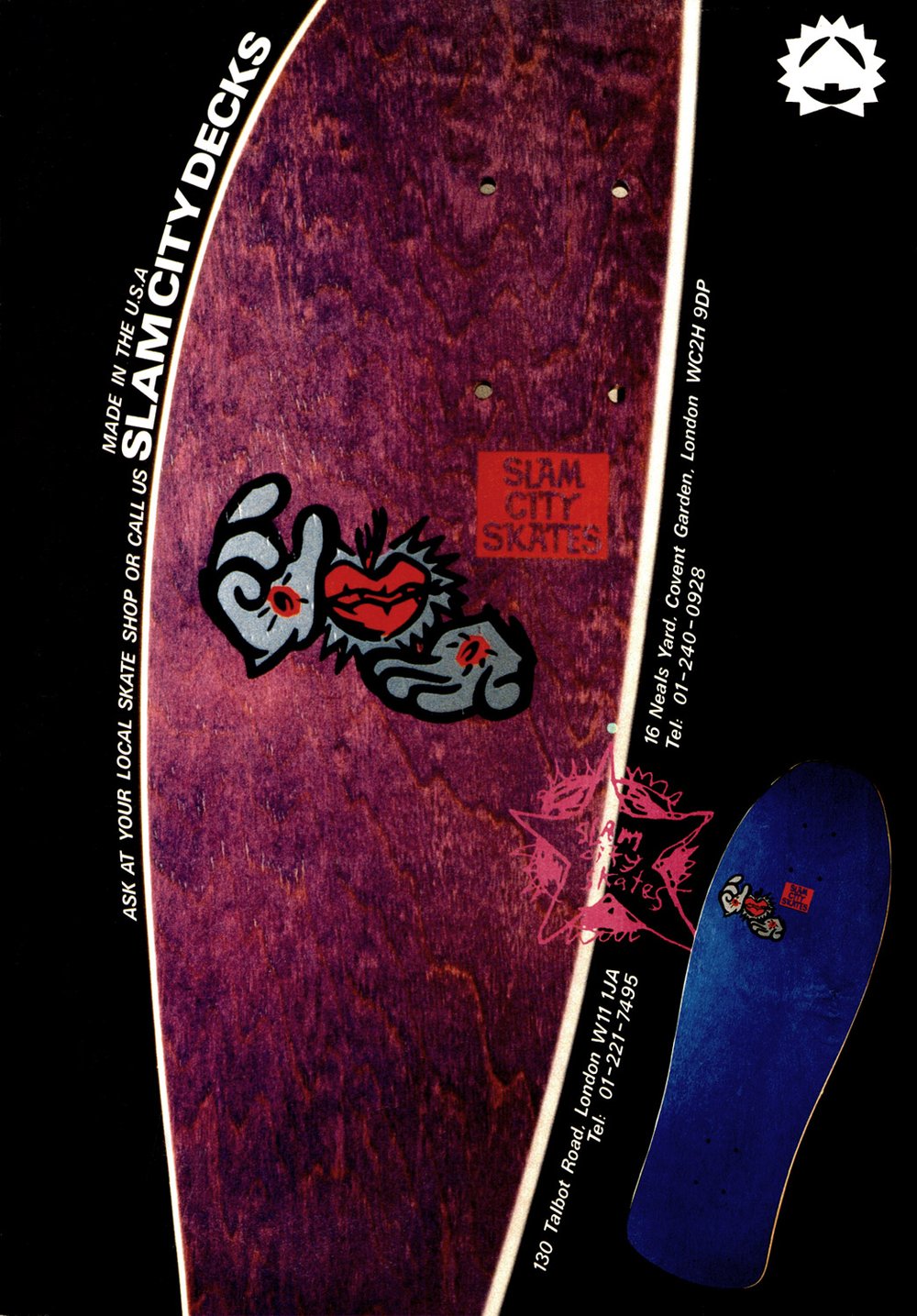

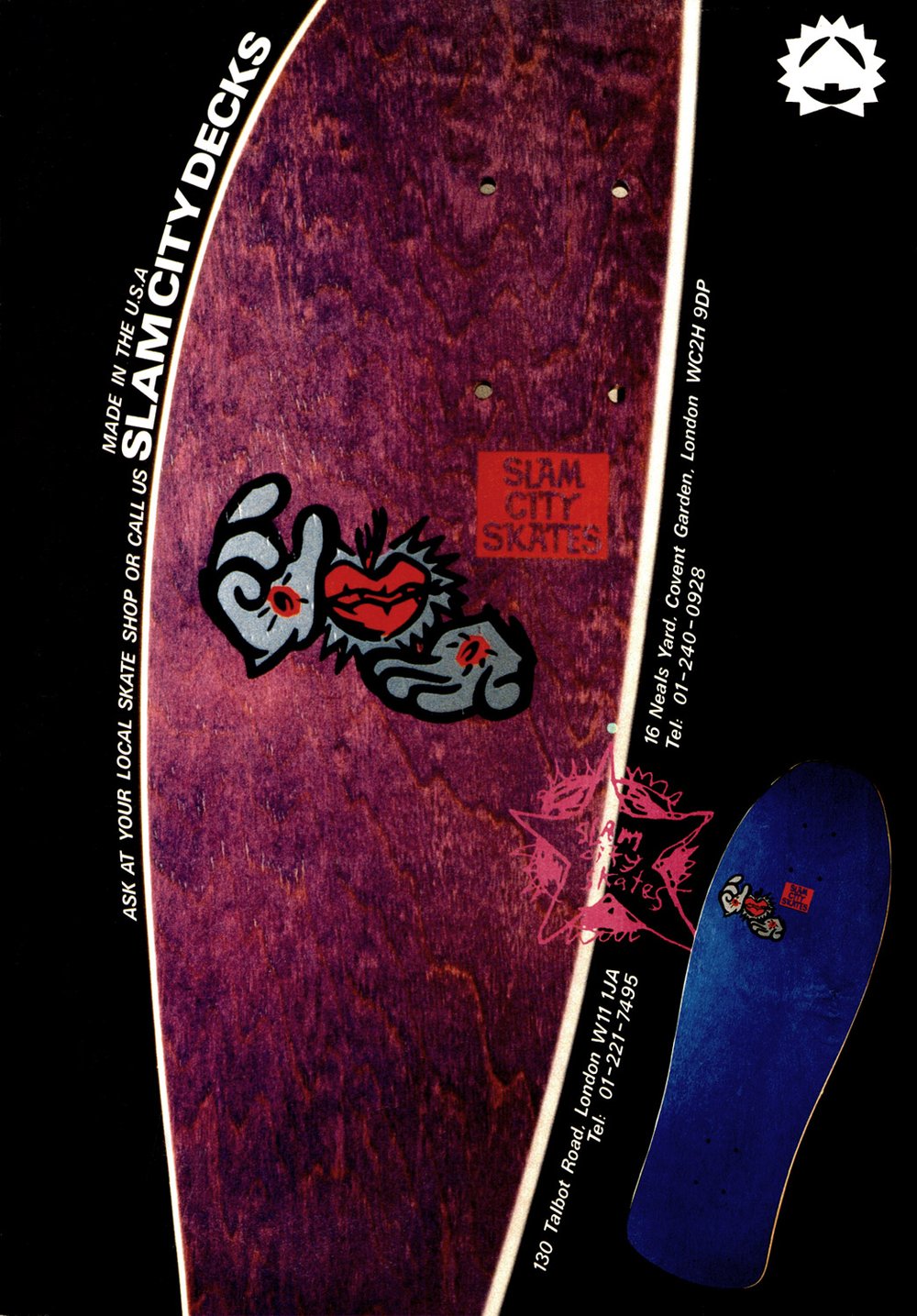

Advertisement from Sidewalk magazine, 1997, featuring Reuben Goodyear. A Home from Home With its relaxed atmosphere and lenient approach to commerce it’s hardly surprising that the staff pushed some boundaries and took some liberties. A lot was tolerated in the early days. One particular phenomenon that illustrates this perfectly, was that of employees sleeping in the shop. This was mostly the result of either a bad hangover or not even making it home from the night before – to many, crashing at the shop was a preferred alternative to the night bus home. “We used to go out to Cheap Skates (student night in Soho) every Wednesday night,” recalled Greg Finch, who worked at Slam between 1999 and 2001. “It was only 60p a drink, and we’d get so hammered that we’d literally be passing out underneath the clothes rails the next day.” Staff would often spend Thursdays sleeping under the T-shirt rail, after showing up to work still drunk. “Because there were so many T-shirts packed into a small space, you could totally get in there, get underneath it and nobody would find you,” said Finch. But not all of the sleeping was booze related. Finch actually slept in the shop for three months while between flats, storing all his stuff behind the board wall and showering at friends’ homes. “I’d get all the jackets and lay them down on the floor and lay a Unabomber sleeping bag on top. I had to make sure I was awake before work started. I’d pack everything up and go out and wait for the first people to come in and then I’d come back in.” Finch got so comfortable there, he actually began inviting people back with him to stay. And when he did finally find a new flat, he got DHL to deliver all his belongings there… on Slam’s bill.  ‘Slam City Decks’ advertisement from RAD magazine, 1990. Disappearing Stock At one point in the ’90s, theft at Slam was spiralling out of control. “It was getting ridiculous, people were sticking boards down their trousers,” recalled Hartwell. What made this particularly irritating, he explained, was that a lot of the stealing was done by friends who had already been hooked-up with discounts or a place on the flow team: “It wasn’t just some random person off the street, it would be someone you knew, and that was just rude.” But the disappearing product wasn’t all stolen. Seth Curtis recalled receiving his first free product back in 1997: “I’d never gotten a free skateboard before, I mean I worked at Sumo (in Sheffield), but that shop was so tiny we paid for boards to help the place out.” One time Mark Baines was down from Sheffield and met up with Curtis after work. Baines suggested they go skating but Curtis had neither his board nor his skate shoes with him, so Sharon (Tomlin, then manager) said he could get a set-up and shoes for free. “I remember going skating and thinking: ‘wow, I just got this for free. This is really weird’,” said Curtis. This tradition of a free board here and there for employees carried on to the late ’90s, but the hook-ups started to get a little out of control with Slam staff gifting boards and other goods to their friends, as well as to themselves. “It was a piss-take,” said Finch. “Everybody was in on it – it wasn’t just a select group of people. It’s a wonder that place survived. The one good thing that came of that, is that a lot of people who were on the skids, who needed boards and wheels and stuff, got hooked up. We created a sort of unofficial flow team of Southbank locals, who were hard on their luck and had no money.” Like all good things however, the era of slippery stock had to come to an end – something had to be done. “When I first started working at Slam it was like a sieve, product was disappearing, free crap was going out all the time,” said Chris Pulman, who arrived as shop manager in 1999. “I definitely tightened it up a lot.”

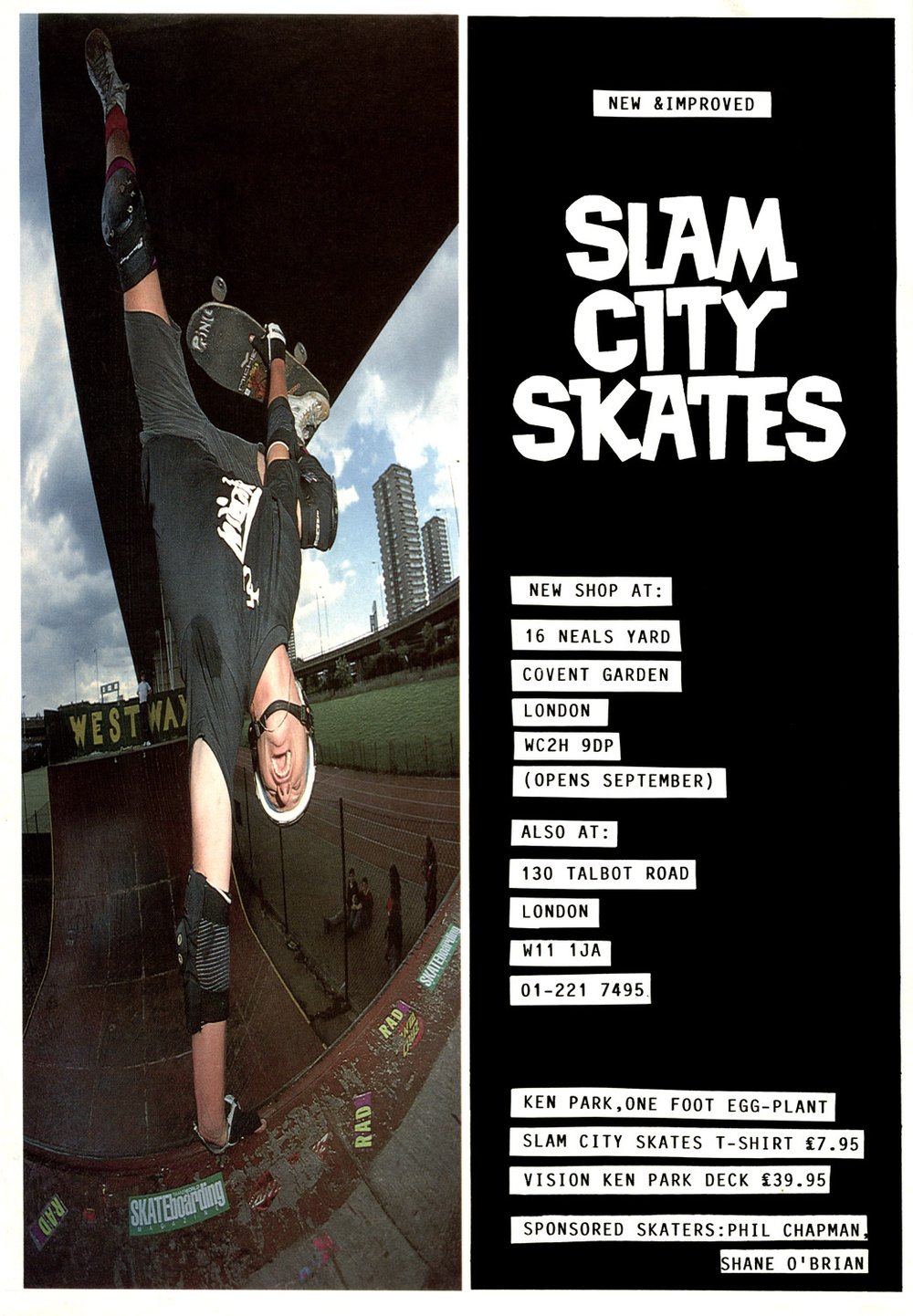

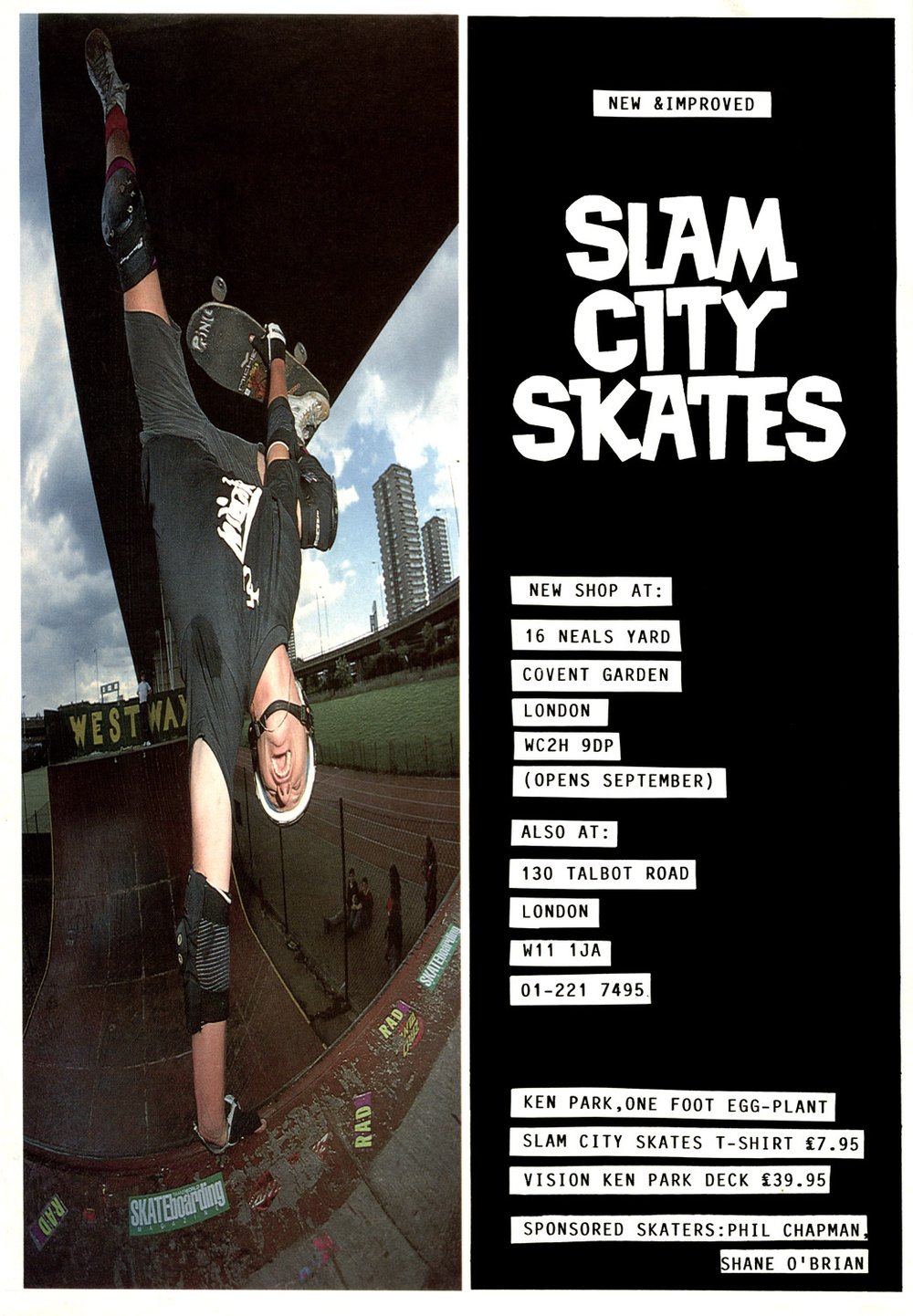

‘Slam City Decks’ advertisement from RAD magazine, 1990. Disappearing Stock At one point in the ’90s, theft at Slam was spiralling out of control. “It was getting ridiculous, people were sticking boards down their trousers,” recalled Hartwell. What made this particularly irritating, he explained, was that a lot of the stealing was done by friends who had already been hooked-up with discounts or a place on the flow team: “It wasn’t just some random person off the street, it would be someone you knew, and that was just rude.” But the disappearing product wasn’t all stolen. Seth Curtis recalled receiving his first free product back in 1997: “I’d never gotten a free skateboard before, I mean I worked at Sumo (in Sheffield), but that shop was so tiny we paid for boards to help the place out.” One time Mark Baines was down from Sheffield and met up with Curtis after work. Baines suggested they go skating but Curtis had neither his board nor his skate shoes with him, so Sharon (Tomlin, then manager) said he could get a set-up and shoes for free. “I remember going skating and thinking: ‘wow, I just got this for free. This is really weird’,” said Curtis. This tradition of a free board here and there for employees carried on to the late ’90s, but the hook-ups started to get a little out of control with Slam staff gifting boards and other goods to their friends, as well as to themselves. “It was a piss-take,” said Finch. “Everybody was in on it – it wasn’t just a select group of people. It’s a wonder that place survived. The one good thing that came of that, is that a lot of people who were on the skids, who needed boards and wheels and stuff, got hooked up. We created a sort of unofficial flow team of Southbank locals, who were hard on their luck and had no money.” Like all good things however, the era of slippery stock had to come to an end – something had to be done. “When I first started working at Slam it was like a sieve, product was disappearing, free crap was going out all the time,” said Chris Pulman, who arrived as shop manager in 1999. “I definitely tightened it up a lot.”  ‘New & Improved’ advertisement from RAD magazine, 1988, featuring Ken Park and introducing Slam’s new shop in Neal’s Yard. Products Through the Ages Despite the theft and freebies a lot of product has been legitimately sold throughout Slam’s history. Countless brands of decks, wheels, trucks, clothing, footwear and accessories have come and gone over the past 25 years. When Will Bankhead first visited Slam on Talbot Road in the ’80s he remembered seeing a Mark ‘Gator’ Rogowski board on the wall: “I’ve seen that in Thrasher,” he said to a friend. Slam was one of the first places in London to carry such a wide range of boards from the States. In the late ’80s and the beginning of the ’90s, stickers were the biggest sellers, according to Waterman: “The most annoying things we sold were stickers. I love them, but we used to sell loads and loads, having to get the sticker book out each time and let these kids paw through it. It was really frustrating – especially if it was busy – but I fully understand it because kids would come in with only a small amount of pocket money.” Other big sellers at the time were Powell Rat Nuts and Cell Block risers, which kids thought would stop their boards breaking. “I saw loads of trends coming and going, said Waterman. “Rip-Grip – that stupid foamy shit all over the board – it would sell like mad. All the kids had to have the right accessory to go on the board. That would amuse me.” In the early ’90s Mike Vallely double-kick boards, Real six packs of wheels, and New Deal boards were top-sellers. Then, a few years later in the mid ’90s, brands like Alien Workshop, DC, and Supreme took over. “We sold loads of that stuff,” said Hartwell, “Vans Half Cabs too, and when Stereo came out that was the new hot shit.” Around 1997, with the help of the Welcome to Hell and Mixtape videos, sales of Toy Machine and Zoo York really took off (Slam was distributing both brands in the UK). Silas was also doing really well at this time. In the early days, Slam was one of only a handful of shops selling the brand worldwide. “When Silas was in the store we just couldn’t keep it in,” recalled Finch. “People would actually offer us more than it was worth so they could take it back to Japan and sell it there, where it was even harder to get hold of.” To combat this unofficial wholesaling, a limit of three or four items of Silas clothing per person was imposed. The early 2000s saw the rise in popularity of UK board brands, a phenomenon witnessed first hand by Chris Pulman: “You’re really close to the scene: watching things like Blueprint grow and watching the guys come in from filming missions at the end of the day when they were making First Broadcast, seeing that people were out there really making a British scene. So we decided to really push it. We sold a ton of Blueprint stuff back then, a ton of Unabomber stuff, and we always kept those boards on the wall.” In addition to Unabomber and Blueprint boards, black éS Accels, Powell Reds and Powell Swiss all sold extensively in the early 2000s. In 2005, Slam collaborated with Nike SB to create the Slam Dunk. Its release saw queues stretching out of the alley almost to Neal Street. Around this time, Slam launched the Nike Kickflip Challenge: “You had two tries to do a kickflip in your new Nikes. If you made one you got a £5 refund,” said Pulman. “It was a sort of tongue-in-cheek up yours to the trainer dudes, a way for us to keep it as core to skateboarding as we could.” Current shop manager Dan Callow explained the importance of the various shoe trends to Slam: “All the different crews got into wearing Dunks – Dunk fever pretty much kept us in business. Then there was the whole DC era before that. Today the Janoski (Nike SB Stefan Janoski) is a phenomenon – it’s crazy to see the amount of Janoskis we sell to all types of people.” Sales in the late 2000s were dominated by brands such as Landscape, Anti Hero, Spitfire, Huf, Vans and Nike SB. These days the biggest selling board brands are Palace and Krooked, while clothing brands Kr3w and Altamont also sell very well. Nike SB remains the shop’s top-selling shoe brand.

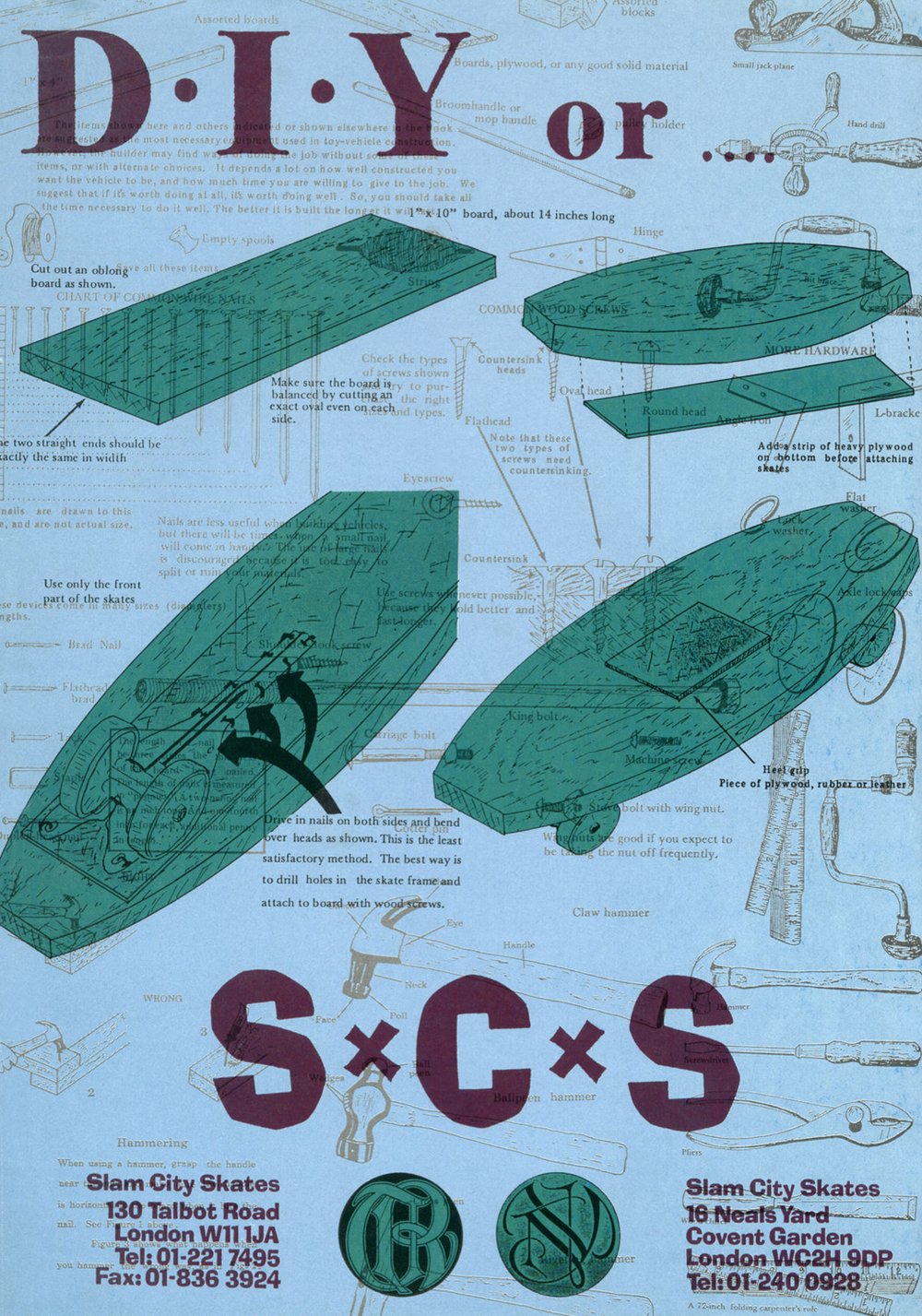

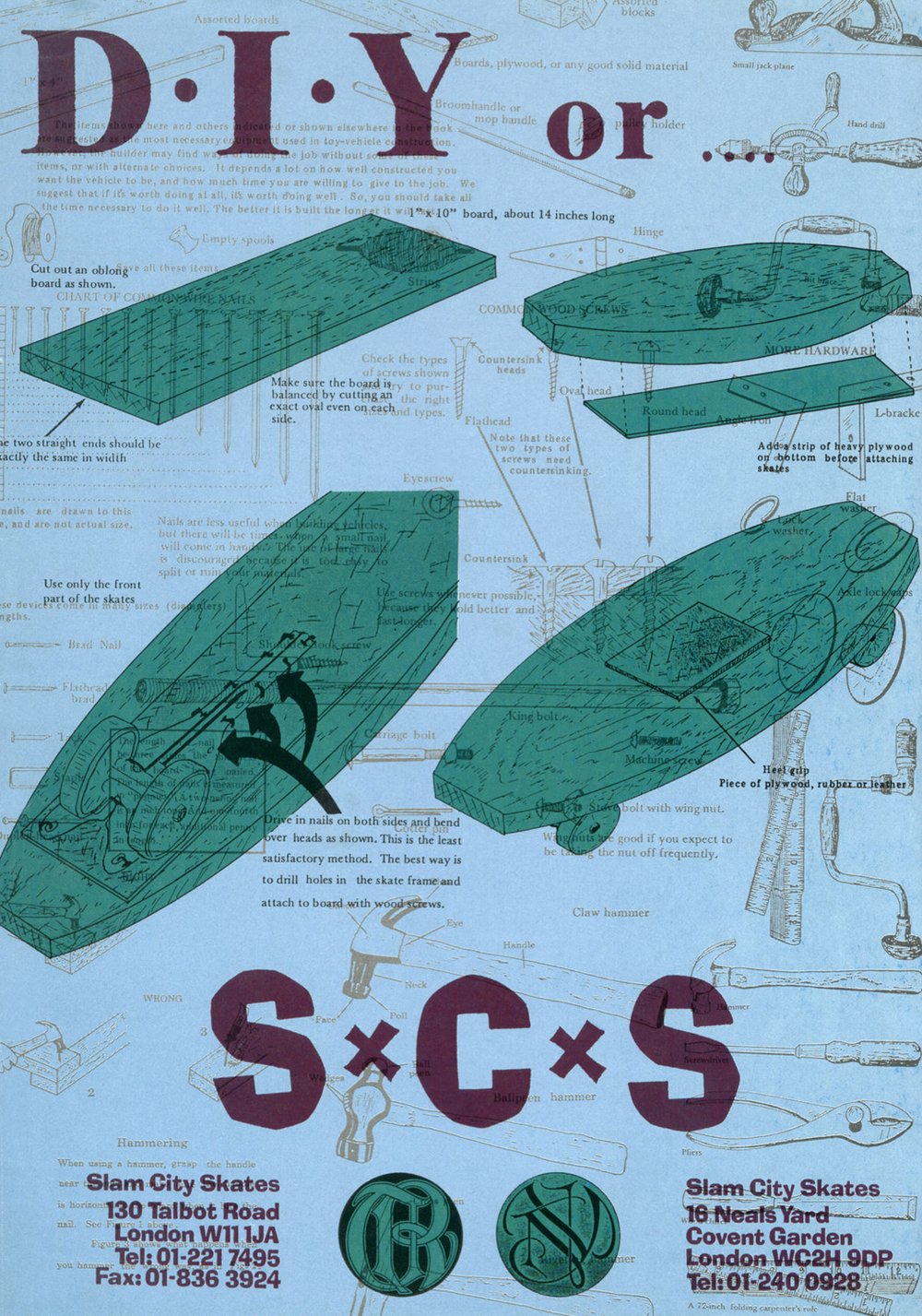

‘New & Improved’ advertisement from RAD magazine, 1988, featuring Ken Park and introducing Slam’s new shop in Neal’s Yard. Products Through the Ages Despite the theft and freebies a lot of product has been legitimately sold throughout Slam’s history. Countless brands of decks, wheels, trucks, clothing, footwear and accessories have come and gone over the past 25 years. When Will Bankhead first visited Slam on Talbot Road in the ’80s he remembered seeing a Mark ‘Gator’ Rogowski board on the wall: “I’ve seen that in Thrasher,” he said to a friend. Slam was one of the first places in London to carry such a wide range of boards from the States. In the late ’80s and the beginning of the ’90s, stickers were the biggest sellers, according to Waterman: “The most annoying things we sold were stickers. I love them, but we used to sell loads and loads, having to get the sticker book out each time and let these kids paw through it. It was really frustrating – especially if it was busy – but I fully understand it because kids would come in with only a small amount of pocket money.” Other big sellers at the time were Powell Rat Nuts and Cell Block risers, which kids thought would stop their boards breaking. “I saw loads of trends coming and going, said Waterman. “Rip-Grip – that stupid foamy shit all over the board – it would sell like mad. All the kids had to have the right accessory to go on the board. That would amuse me.” In the early ’90s Mike Vallely double-kick boards, Real six packs of wheels, and New Deal boards were top-sellers. Then, a few years later in the mid ’90s, brands like Alien Workshop, DC, and Supreme took over. “We sold loads of that stuff,” said Hartwell, “Vans Half Cabs too, and when Stereo came out that was the new hot shit.” Around 1997, with the help of the Welcome to Hell and Mixtape videos, sales of Toy Machine and Zoo York really took off (Slam was distributing both brands in the UK). Silas was also doing really well at this time. In the early days, Slam was one of only a handful of shops selling the brand worldwide. “When Silas was in the store we just couldn’t keep it in,” recalled Finch. “People would actually offer us more than it was worth so they could take it back to Japan and sell it there, where it was even harder to get hold of.” To combat this unofficial wholesaling, a limit of three or four items of Silas clothing per person was imposed. The early 2000s saw the rise in popularity of UK board brands, a phenomenon witnessed first hand by Chris Pulman: “You’re really close to the scene: watching things like Blueprint grow and watching the guys come in from filming missions at the end of the day when they were making First Broadcast, seeing that people were out there really making a British scene. So we decided to really push it. We sold a ton of Blueprint stuff back then, a ton of Unabomber stuff, and we always kept those boards on the wall.” In addition to Unabomber and Blueprint boards, black éS Accels, Powell Reds and Powell Swiss all sold extensively in the early 2000s. In 2005, Slam collaborated with Nike SB to create the Slam Dunk. Its release saw queues stretching out of the alley almost to Neal Street. Around this time, Slam launched the Nike Kickflip Challenge: “You had two tries to do a kickflip in your new Nikes. If you made one you got a £5 refund,” said Pulman. “It was a sort of tongue-in-cheek up yours to the trainer dudes, a way for us to keep it as core to skateboarding as we could.” Current shop manager Dan Callow explained the importance of the various shoe trends to Slam: “All the different crews got into wearing Dunks – Dunk fever pretty much kept us in business. Then there was the whole DC era before that. Today the Janoski (Nike SB Stefan Janoski) is a phenomenon – it’s crazy to see the amount of Janoskis we sell to all types of people.” Sales in the late 2000s were dominated by brands such as Landscape, Anti Hero, Spitfire, Huf, Vans and Nike SB. These days the biggest selling board brands are Palace and Krooked, while clothing brands Kr3w and Altamont also sell very well. Nike SB remains the shop’s top-selling shoe brand.  ‘DIY or SCS’ advertisement from RAD magazine, 1989 Bad Reputation Over the years, for whatever reason, Slam has a gained a reputation for being an intimidating place. Waterman explained why some might have experienced bad vibes during his tenure: “Sometimes we had total idiots working behind the counter who thought it was a really important position and that they could therefore look down on everyone else, kind of the same as in record shops. But at the same time, if it was really busy, it would be really hard to keep a super-smiley face, especially when you have irate parents who don’t understand that it takes half an hour to set up a board.” Sawyer explained further: “Everybody who works in a shop has their own shit going on. So you could be having a bad day and a fully-grown man can come in and ask: ‘what shoe size am I?’ and maybe you’re not inclined to mollycoddle.” One legendary incident saw an unnamed employee hang up on a customer after shouting: “WE SELL SKATEBOARDS, WE SELL SKATEBOARDS, WE SELL SKATEBOARDS” down the phone. The customer had dared to ask if Slam stocked rollerblades, roller skates or ice skates. Things have definitely improved over the years however, and today Slam is more of an inviting place than perhaps it once was. “It’s just a really good skateboard shop,” said Pulman. “The people in there do know what they are talking about, so it’s always going to be a little intimidating to go in. I think maybe people place their intimidation and fear of going into Slam onto the staff, when most of it’s just in the people themselves.”

‘DIY or SCS’ advertisement from RAD magazine, 1989 Bad Reputation Over the years, for whatever reason, Slam has a gained a reputation for being an intimidating place. Waterman explained why some might have experienced bad vibes during his tenure: “Sometimes we had total idiots working behind the counter who thought it was a really important position and that they could therefore look down on everyone else, kind of the same as in record shops. But at the same time, if it was really busy, it would be really hard to keep a super-smiley face, especially when you have irate parents who don’t understand that it takes half an hour to set up a board.” Sawyer explained further: “Everybody who works in a shop has their own shit going on. So you could be having a bad day and a fully-grown man can come in and ask: ‘what shoe size am I?’ and maybe you’re not inclined to mollycoddle.” One legendary incident saw an unnamed employee hang up on a customer after shouting: “WE SELL SKATEBOARDS, WE SELL SKATEBOARDS, WE SELL SKATEBOARDS” down the phone. The customer had dared to ask if Slam stocked rollerblades, roller skates or ice skates. Things have definitely improved over the years however, and today Slam is more of an inviting place than perhaps it once was. “It’s just a really good skateboard shop,” said Pulman. “The people in there do know what they are talking about, so it’s always going to be a little intimidating to go in. I think maybe people place their intimidation and fear of going into Slam onto the staff, when most of it’s just in the people themselves.”  ‘Keith was stoked on his new tag’ advertisement from Sidewalk magazine, 1996, part of a series by James Jarvis. Slam Today Slam City Skates has come a long way in its first 25 years. From its humble beginnings at Rough Trade in west London with a few boards behind the counter, to the present day with two shops in central London, it’s safe to say Slam has flourished. With new owners Gareth Skewis and Marshall Taylor taking the reins, the legacy of this London skate shop continues on. Chris Pulman, who recently returned to Slam as business manager, described Slam today: “It’s a much larger business with multiple shops, the mail order business has increased and now we produce a lot more things. We have ‘Hold Tight’ Henry (Edwards-Wood) and a whole lot of rad people involved with Slam now.” In early 2012, Slam plans to release its first ever full-length skate film, directed by Henry Edwards-Wood. City of Rats will feature the Slam City team along with dozens of other friends and London locals. Slam has a newly designed website and there are future projects with shoe companies planned, along with collaborations with Real, Spitfire and Cliché. The Slam clothing line continues to grow with designs by local artists such as James Jarvis and Fergadelic, among others. The Slam crew has a lot in the works for 2012, so stay tuned.

‘Keith was stoked on his new tag’ advertisement from Sidewalk magazine, 1996, part of a series by James Jarvis. Slam Today Slam City Skates has come a long way in its first 25 years. From its humble beginnings at Rough Trade in west London with a few boards behind the counter, to the present day with two shops in central London, it’s safe to say Slam has flourished. With new owners Gareth Skewis and Marshall Taylor taking the reins, the legacy of this London skate shop continues on. Chris Pulman, who recently returned to Slam as business manager, described Slam today: “It’s a much larger business with multiple shops, the mail order business has increased and now we produce a lot more things. We have ‘Hold Tight’ Henry (Edwards-Wood) and a whole lot of rad people involved with Slam now.” In early 2012, Slam plans to release its first ever full-length skate film, directed by Henry Edwards-Wood. City of Rats will feature the Slam City team along with dozens of other friends and London locals. Slam has a newly designed website and there are future projects with shoe companies planned, along with collaborations with Real, Spitfire and Cliché. The Slam clothing line continues to grow with designs by local artists such as James Jarvis and Fergadelic, among others. The Slam crew has a lot in the works for 2012, so stay tuned.