Previous post

Words: Kingsford

City Mill Skate (CMS) is a research project commissioned and funded by University College London (UCL) with the end goal of building a series of skateable ‘dots’ on its new campus in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in east London. The project was well under way with a full programme for 2020 when coronavirus hit the UK. That event was cancelled and Esther Sayers and Sam Griffin of CMS had to quickly rethink the whole programme of activities, including a crucial series of group workshops to design the skate dots. One year on from the UK’s first lockdown, I caught up with Sam and Esther for a chat about the project and its origins, the context of the Olympic Park, how they managed to save CMS by adapting to the pandemic and what they learned along the way.

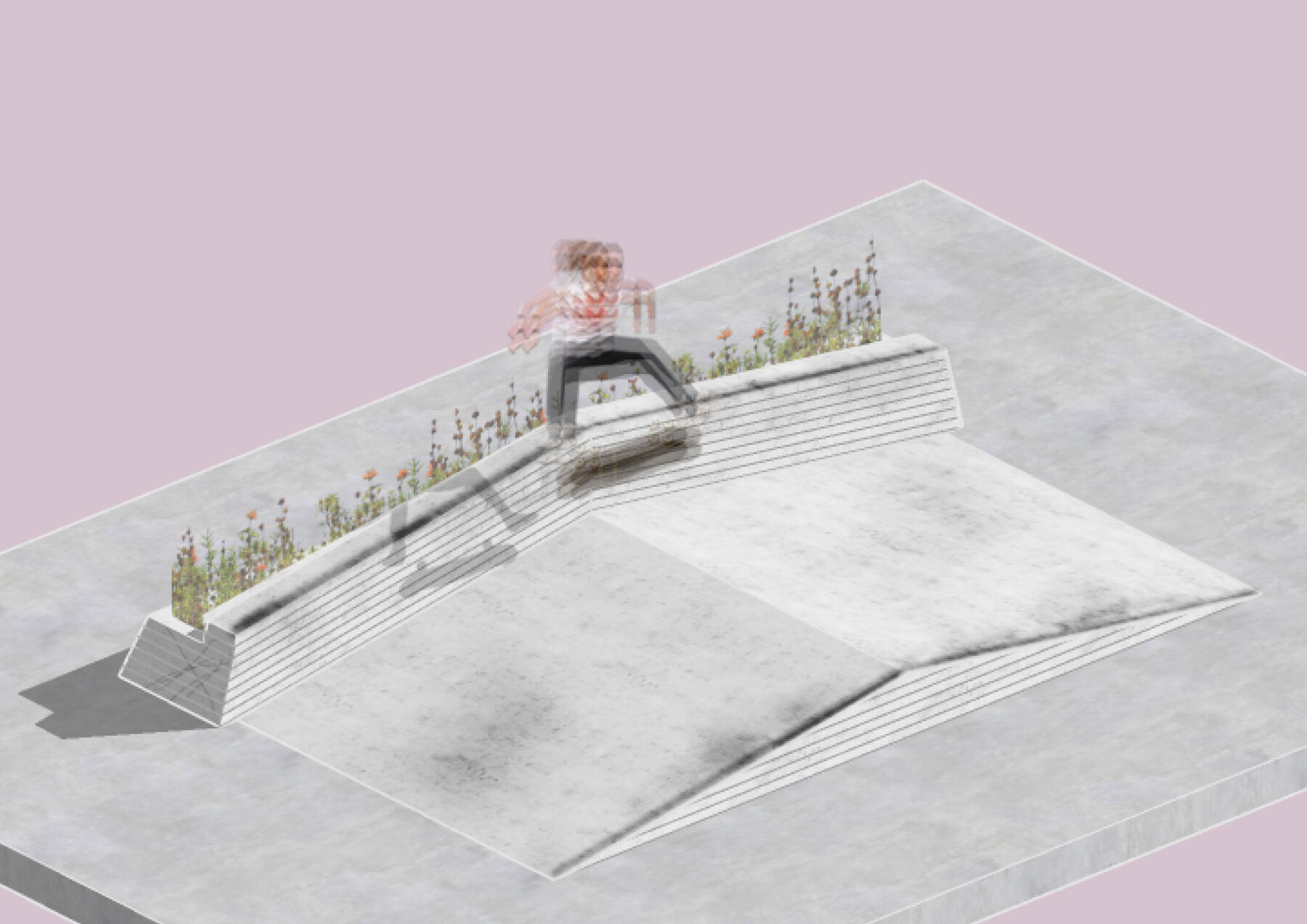

What are skate dots? This seemed like a good place to start. “We don’t actually know yet. That’s the point,” said Sam, “… and it’s not for Esther and us to decide. We are just custodians of a process.” The skate dot is a working title, a play on ‘skate spot’. It’s an incidental feature in a landscape akin to a piece of street furniture in scale and configuration. Sam used the analogy of London Wall in the City of London. He and I used to skate a series of spots along the wall with our friends, moving on to the next one if we were busted or grew bored. “It’s that kind of thing; it’s these little punctuations in a landscape that kind of capture that spirit… of street skating.” Sam explained further: “The skate dot is an object that can sit in the public realm and in an ideal world if it was seen by someone who didn’t skate, they might not necessarily recognise it as a skateable obstacle, but to a skater it’s got a world of really interesting possibilities. But it’s a punctuation, it’s not an environment.” Esther added her own analogy, that of a sculpture in a sculpture trail. “You don’t really know that you’re going to come across it but once you do… you’ve got to shift your way of thinking and seeing it in order to conceptually understand it,” she explained.

When I first heard about CMS I was surprised for two reasons. Firstly, in spite of Bartlett professor Iain Borden’s widely referenced work on skateboarders’ use of spaces and architecture not intended for them, you are almost always moved on from skating UCL’s Bloomsbury campus. Secondly, skateboarding and the Olympic Park have a problematic history, but more on that later. I asked Esther and Sam about UCL’s motivation for commissioning and funding the project.

Esther explained that the university is keen to engage with the communities living close to its new campus, rather than “sort of parachuting in and taking over… City Mill Skate is just one thing that UCL Culture are doing in the area to try and bridge that gap and to do something which is more about the cultural engagement of the local community rather than an imposition.” Sam explained that UCL is aware that as a Russell Group institution spending hundreds of millions of pounds at the meeting point of three of London’s poorest boroughs, it needs to think creatively about how it engages with the local population. CMS is part of a number of initiatives “which are attempting to… create places and spaces, which may be of interest to people who haven’t either thought of themselves as being academic or even athletic in any particular way,” he added. “UCL were particularly interested in… skateboarding… because skateboarding is a great leveller. It’s not like sailing – you can’t buy your way into it. The entry barriers for skateboarding are very low and skateboarding is very non-discriminatory. It’s not predicated on class…”

UCL is also interested in the life skills skateboarding offers. “That process of learning how to learn and being prepared to fail and understanding you have to fail to succeed and stuff like that but also… that even if you can’t learn something in five to 10 minutes, that’s OK,” said Sam. “I think they’re very interested in that because you need a lot of those skills to maybe get the best out of tertiary education.” Esther was keen to highlight the importance of the research component of CMS to UCL: “It is not just a cultural project, but it is research into what people think, it’s research that builds participation and that gets more understanding of skateboarding and its impact on wellbeing and ecology and all these other themes that come up within other parts of the university… It contributes to knowledge exchange, which is the big buzzword in universities at the moment.

James Davis describes the problematic history of skateboarding and the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in his powerful 2018 opinion piece ‘Street League is not for Free’. To summarise briefly, the park opened in 2013 / 2014 with no facilities for skateboarding. The much-loved Frontside Gardens skatepark in nearby Hackney Wick was an Olympic legacy initiative (it was built by Andy Willis using materials left over from construction of the Olympic Park), supported temporarily by Google before being turned over to developers early in 2017. Frontside locals then built the Wickside DIY across the canal just inside the park but this was demolished without notice or consultation in December 2017, just six months before the neighbouring Copperbox Arena hosted Street League for the first time, for which a skatepark was built and immediately taken down with no opportunity for local people to use it. By contrast, Barcelona’s Street League facility doubles as a free public skatepark year round. Today the Hackney Bridge development occupies the old Wickside site. Despite requests for a skatepark during public consultation and years of committed lobbying by skateboarders, there is to date still no skate facility on the site. Last but by no means least, skateboarding, an Olympic sport, is banned everywhere in the Olympic Park.

I asked Esther how she viewed all this as a relative newcomer to skateboarding. “I find the idea that you can’t skate somewhere shocks me every time I come across it because… I’m not very good at being told not to do something,” she replied. “My agenda with skateboarding is so much about the positive, the learning, the wellbeing, the health… the idea that it’s seen negatively seems so contrary to my experience of skateboarding and all its facets around community cohesion and the culture around it, that I’m surprised… that it’s seen as antisocial still.” I was curious how it was working with the London Legacy Development Corporation (the body overseeing the Olympic Park) on a skateboarding project considering the ban and the history outlined above. “We’ve met with them a few times and Sam Wilkinson and the UCL Culture team are very closely connected to them,” Esther explained. “Because we’ve got a legitimacy around what we’re doing, we can use that to influence people who might find raw skateboarding… rather difficult to handle or want to ban it. It’s… easier sometimes for a councillor or other non-skateboarding official to see the positives when I’m talking to them because I don’t fit the stereotype that they’ve got in their heads about what a skateboarder is,” she added. Skateboard GB and World Skate have shown interest in CMS recently, organisations which could be “quite powerful levers when it comes to demonstrating the benefits of skateboarding,” according to Esther. “I think in a way we are kind of building up a set of people who can speak on our behalves,” she added.

CMS has just released a film City Mill Skate Dots and Lockdown to coincide roughly with the one-year anniversary of the UK’s first coronavirus lockdown. I asked Sam and Esther about the first lockdown, which was imposed on March 23 2020, and its impact on the project. By this point they had secured funding, written a timeline of programming and activities for 2020, produced an article for the Urban Pamphleteer and a poster outlining the pilot research they had carried out in 2019 and organised a launch event in the Olympic Park for March 25, which was of course cancelled. Sam and Esther realised they had to work quickly to save the project. If they couldn’t do anything during lockdown, there was a real danger that the project could be folded. They initiated emergency talks with Daryl Nobbs (Betongpark and Hackney Bumps Group). “We had a kind of odd moment of sort of trying to look into a crystal ball and think very, very quickly on the fly about what the short, mid and long-term implications for lockdown might be, how it would change people’s ability to carry on as usual… and how we would still be able to connect with the people we’d always wanted to talk to, but to do it in a meaningful way that was still safe,” explained Sam. The initial plan to hold workshops at the Bartlett School of Architecture in Here East, where groups would take part in Blue Peter-style making sessions to create the skate dots was off the cards, but the group realised that this element of the project was actually more important than ever, as Sam explained: “People might not be able to skate and they might be looking for a creative outlet to do something. They might feel very isolated. They might feel just bored. That was where the thinking started to ruminate around this idea of kits.”

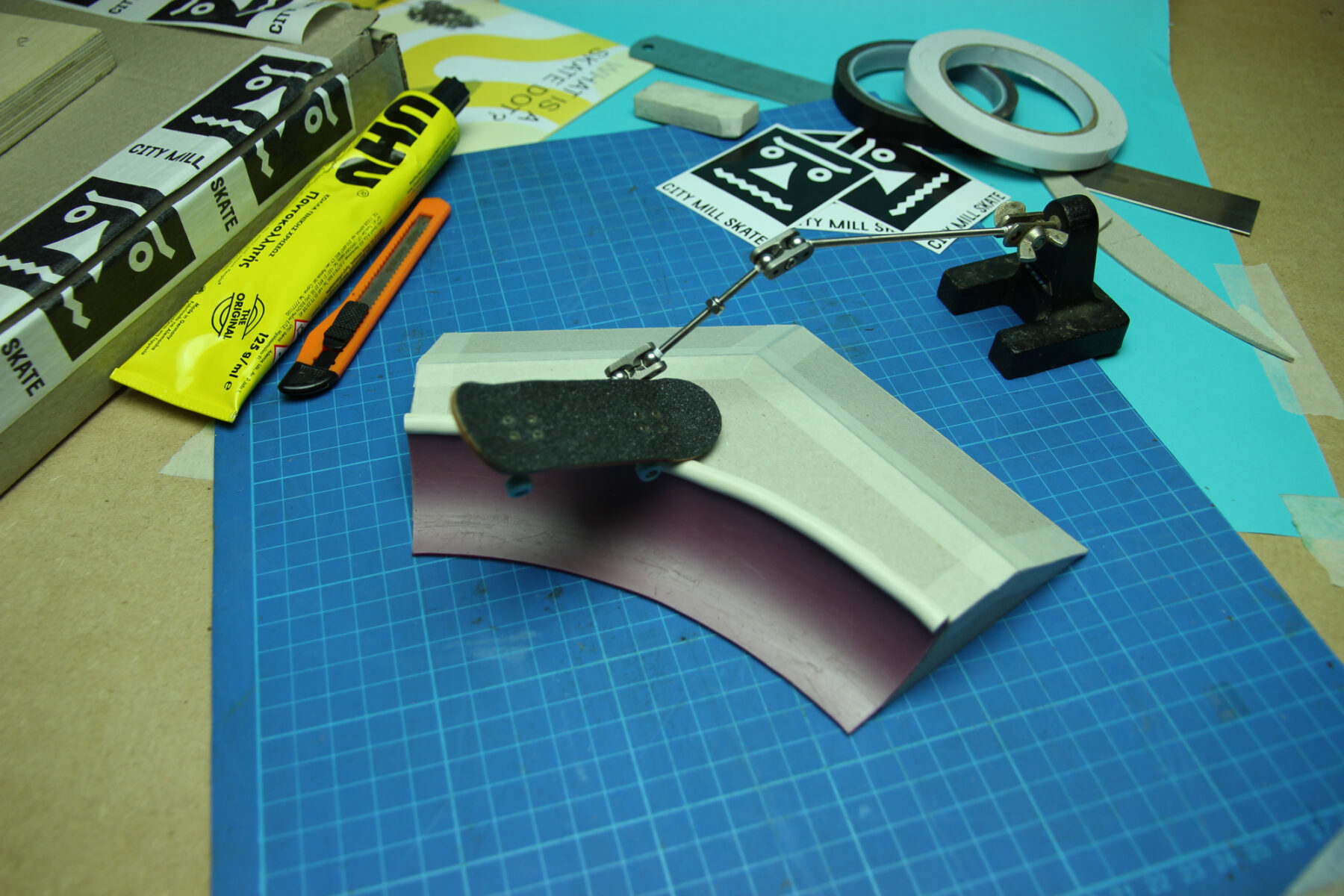

The idea behind the kits was to send skaters materials they needed to get practically involved in designing skate dots, then ask them to send back images of the things they had made. “All was not lost, we didn’t have to retreat into a digital world. We could still work with stuff,” said Esther. The kits were carefully planned and beautifully presented. “We got the branded tape designed, we got the stickers made up and crucially within the inventory of the kits, there’s a lot of stuff that people could keep as well,” added Sam. Sourcing the components during lockdown was easy – lots came from a model making shop run by some helpful old enthusiasts who took an interest in the project – but packing was tricky due to social distancing. All this work had to be done at Esther’s house with help from her family, who also helped her hand deliver most of the kits, for environmental reasons but also to offer the recipients some much-needed human contact, albeit at a safe distance. “It was a very well-intentioned thing. We did manage to catch quite a lot of people,” said Esther.

Recipients were very happy to receive the kits three months into the first lockdown, as one model maker Dougal Marwick describes in the film: “It was a project and like if you’re not working or going to work, not skating, you’re not really seeing your friends, it’s quite nice to have an outlet.” Sam explained how the group wanted the kits to feel like a care package: “You know, like you’d get a package from a sponsor. So something that’s going to get you really stoked, excite you creatively but also to let you know that there are people out there who want to talk to you, they value what you’ve got to say.” Kits were distributed via an open call through an Eventbrite page. Twice as many people applied than kits were available. I asked how the group ensured representation of different groups within London’s wider skateboard community when choosing recipients. “We decided first of all that we wanted as equal gender representation as possible,” explained Esther, “So that meant that we actually accepted all women, all the females who applied… then amongst everyone else, we selected everyone who was under 18, because we wanted young people to be represented… Anybody with a disability went into our yes group and of anyone else, we did it by postcode, because it was about local as much as possible.”

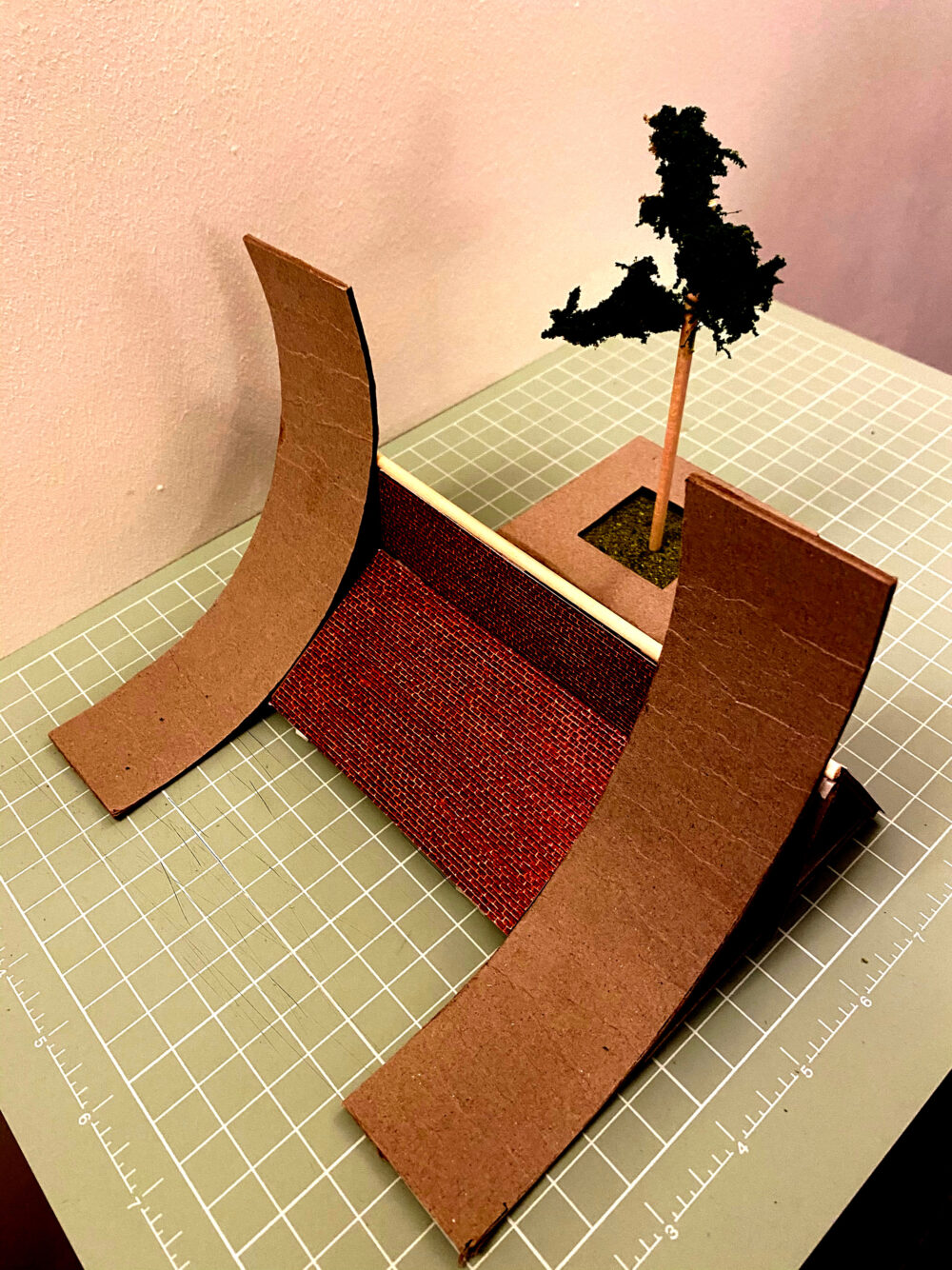

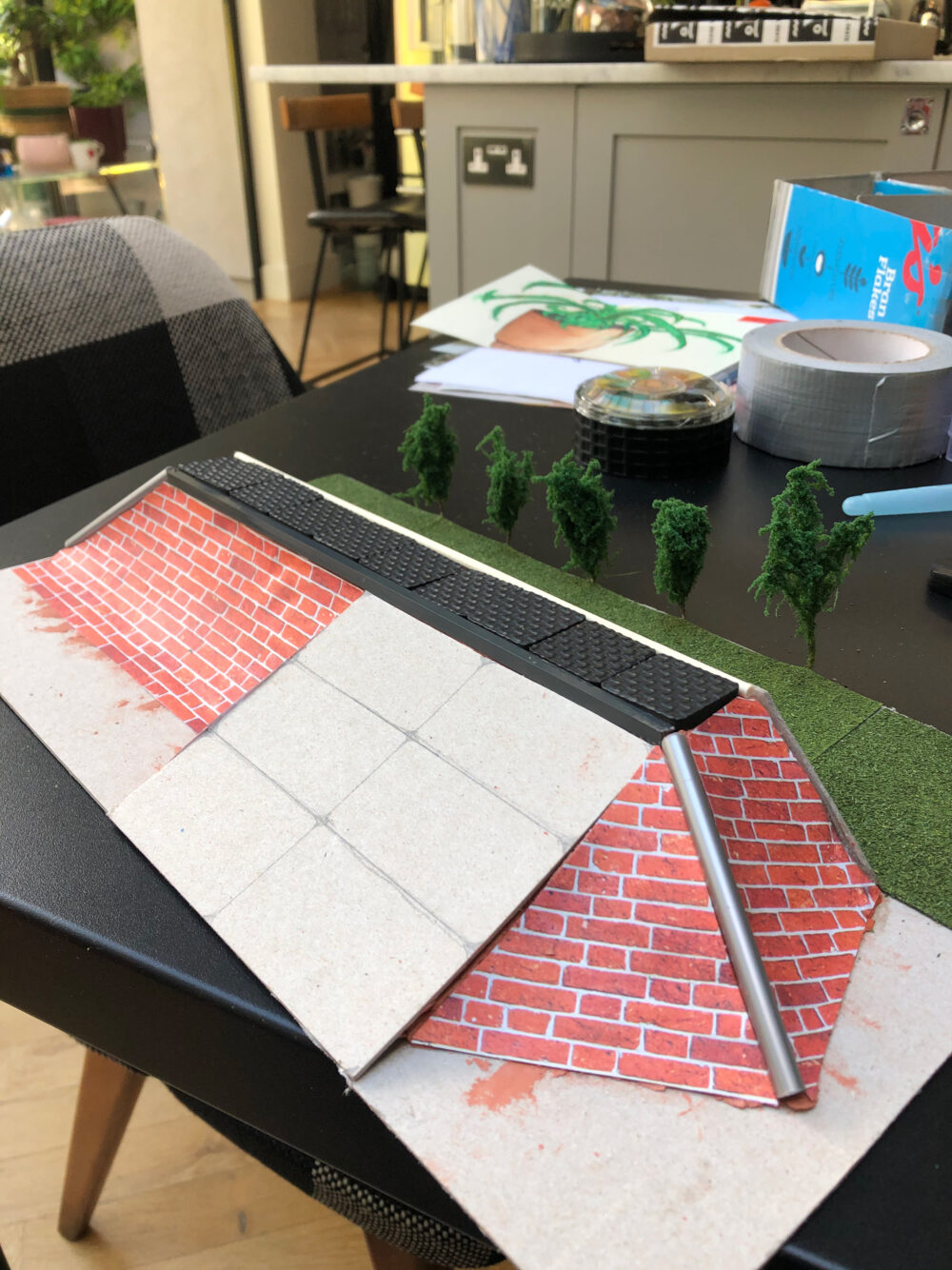

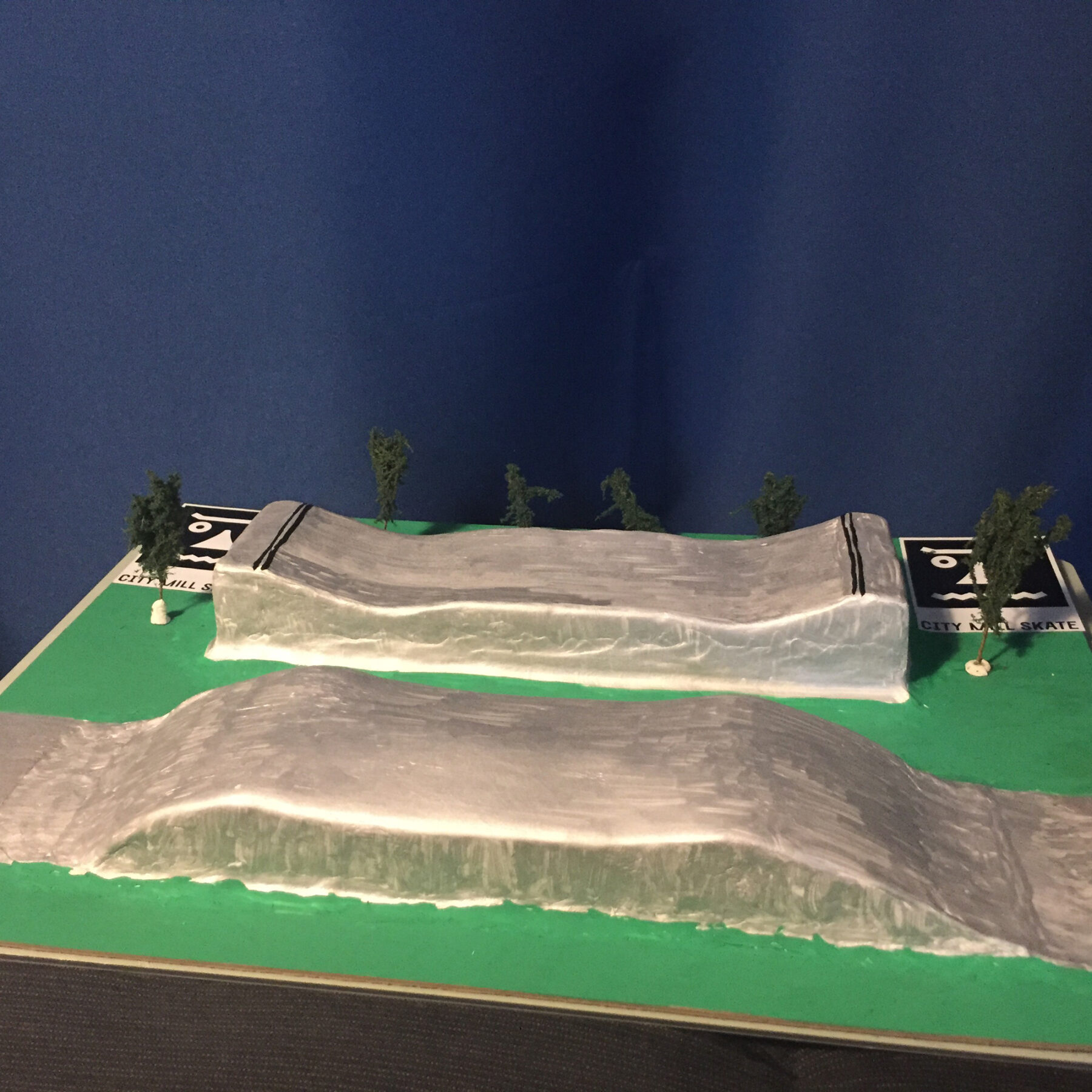

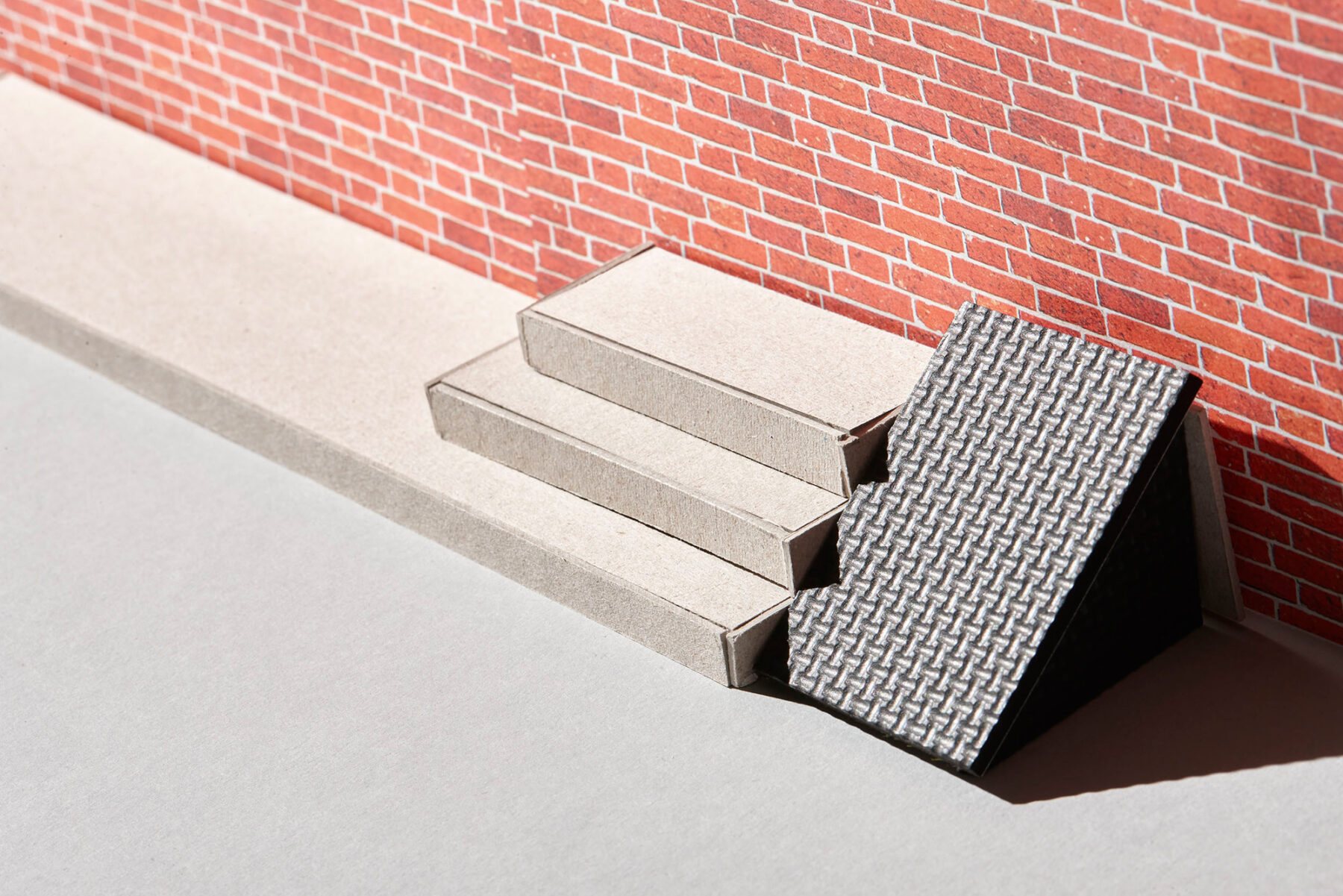

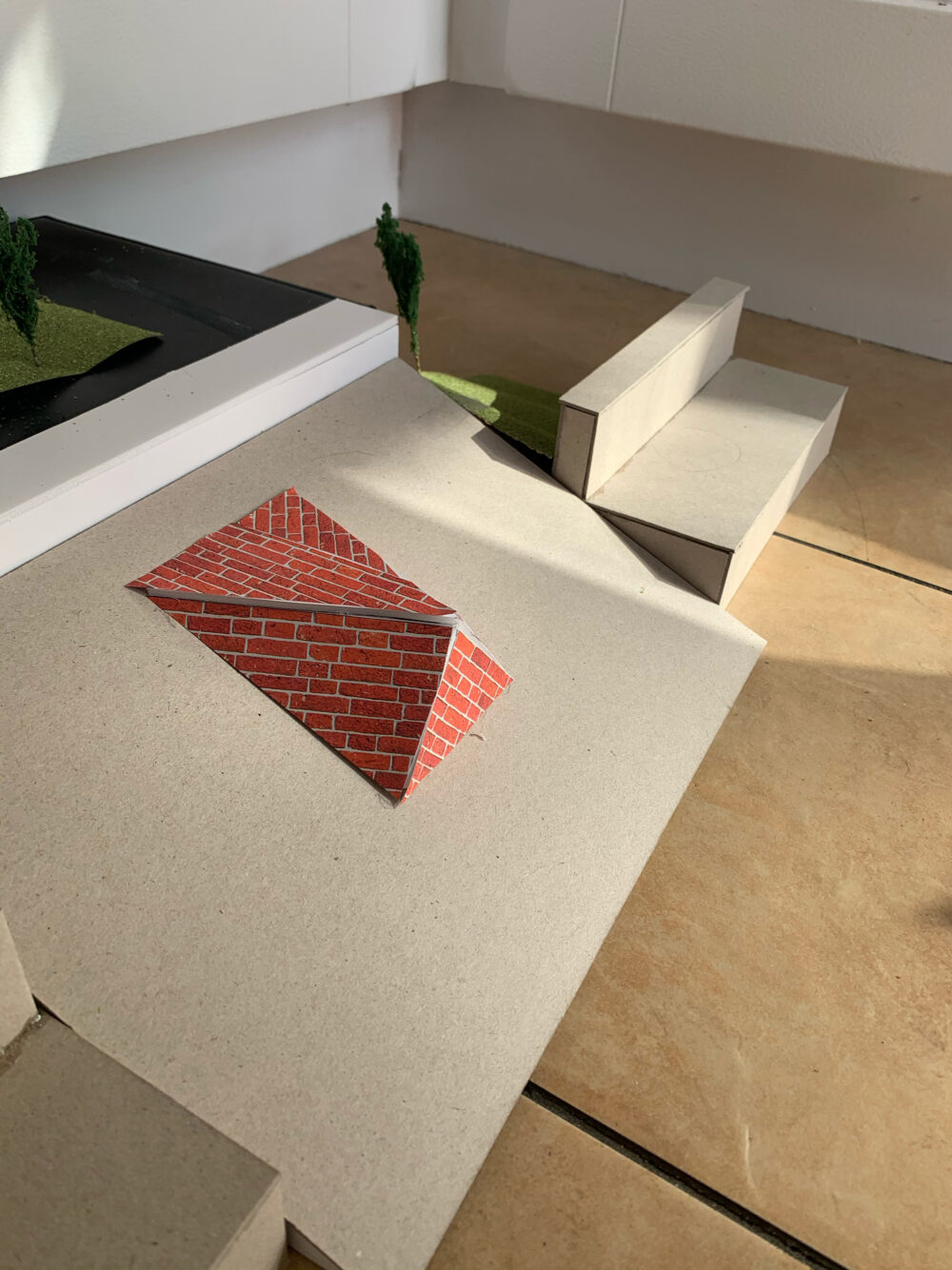

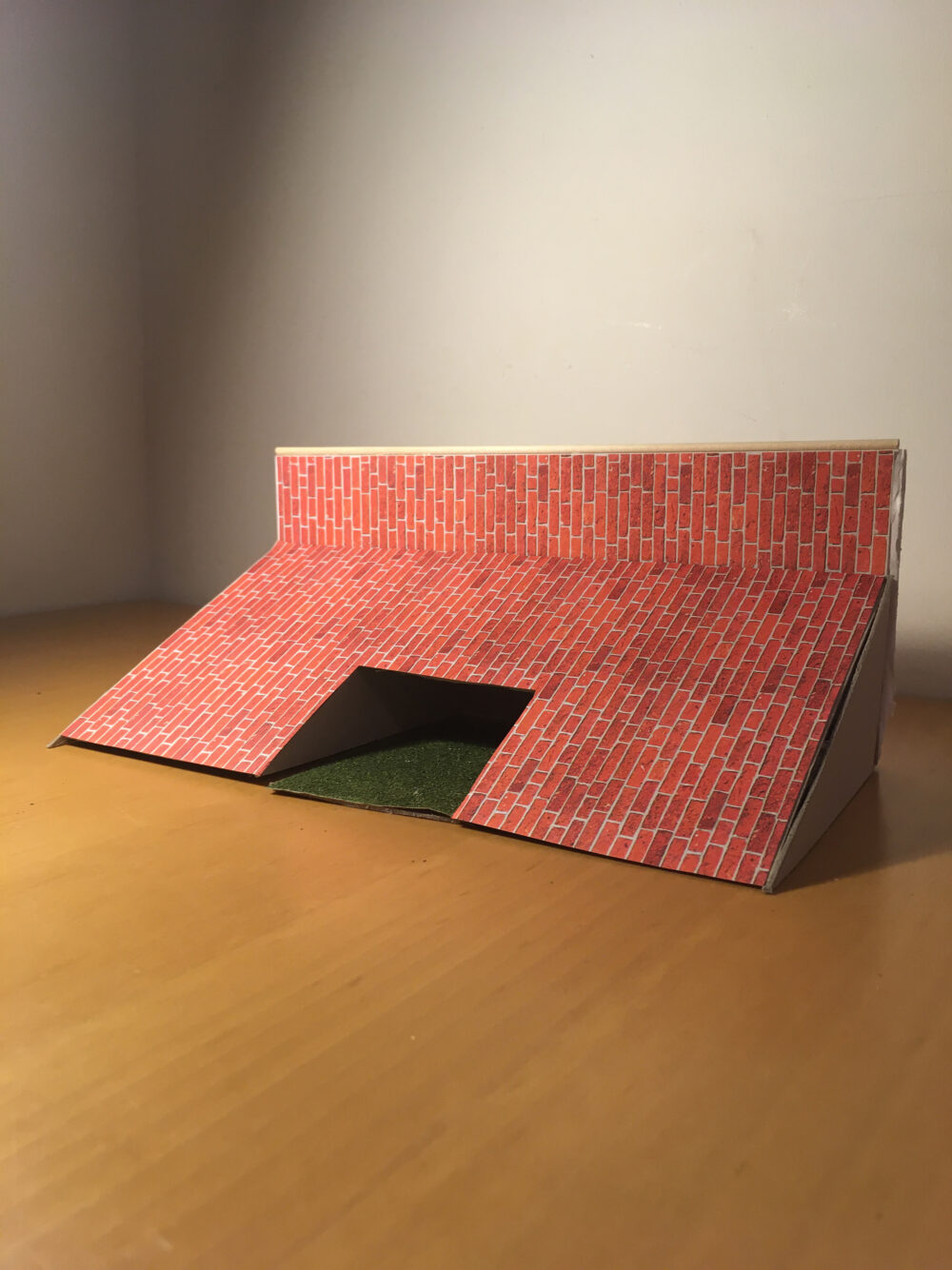

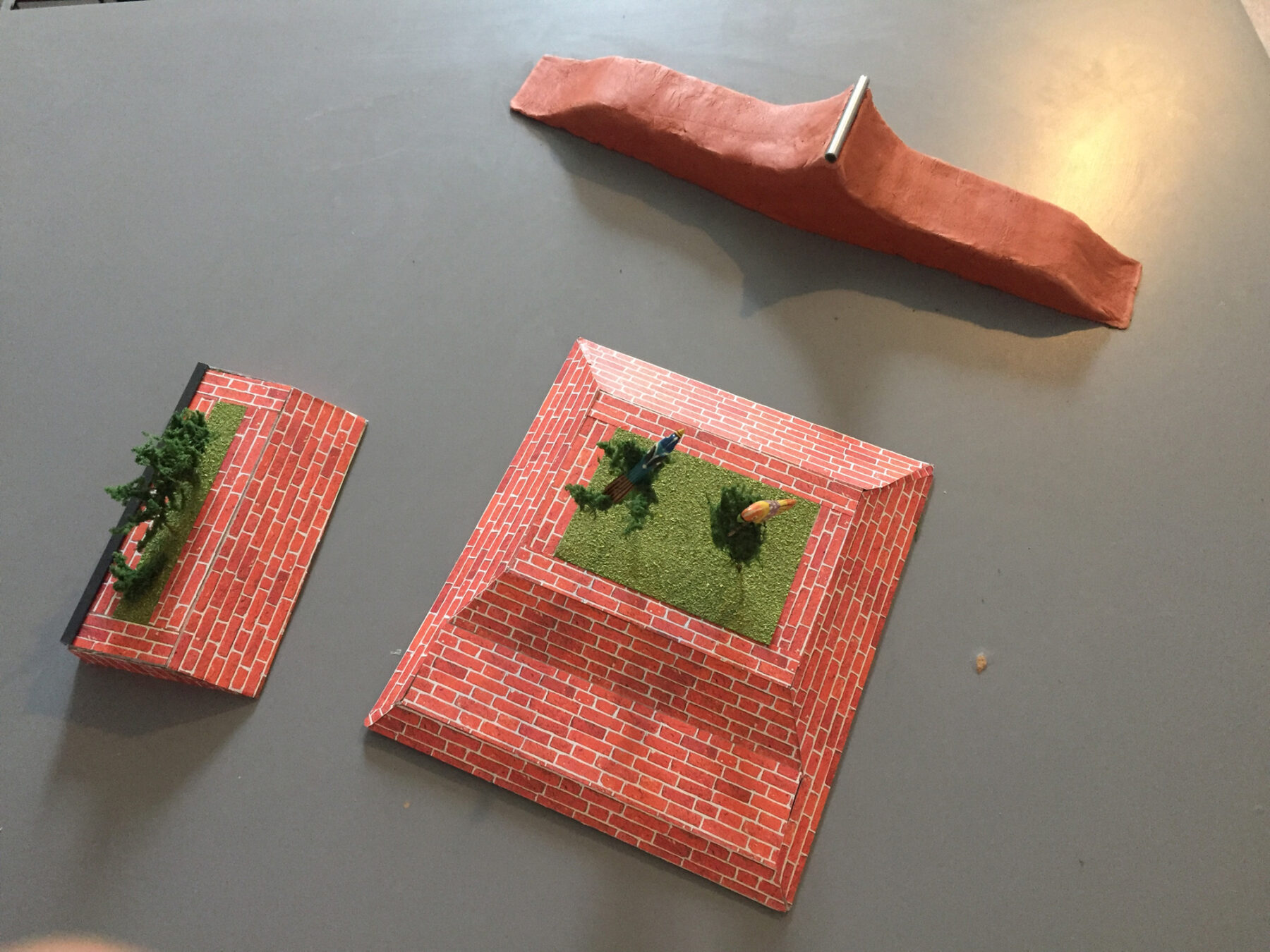

I asked if Sam and Esther had any expectations of what the model makers would create. They didn’t according to Sam, who reiterated his and Esther’s role as custodians guiding a process. They got great stuff across the board, but some of the more interesting stuff came from the girls and women, “because the guys were maybe plugging into more established vernaculars about what they would want to see,” Sam added. “I’m thinking about Emily Badescu’s stuff and Helena Long made some stuff for us and it was brilliant… either things were super interesting as a whole, or… it would just have an element in it and you’d just think: “Christ, why has no one thought if that?”” The variety of responses to the materiality of the kits surprised Esther. The fact that people had to use clay and card meant that the models took on their own look and feel different to the concrete we are used to, which was of particular interest to Esther, who teaches art. This was intended, according to Sam, who explained that the materials in the kit were chosen to: “encourage people tacitly to bust out of any sort of traditional skatepark design. We included textured papers in there, so people could make stuff to look like it had brick on it… There was flexible coping material and solder material so people didn’t just have to make obstacles with coping that was straight.”

In City Mill Skate Dots and Lockdown one of the model makers Lizzie Heath suggests that the process of making models alone, at home during lockdown yielded different results to those that might have been achieved at the planned group workshops: “If you’re in a group with other people, you’d be more creating a space that’s informed by the other things people are making.” Esther agreed, highlighting the tendency in group workshops to look at what other people are doing and take inspiration. Sam suggested that the responses were more personal and that because there wasn’t the static timeframe of a group workshop, “People have been able to kind of ruminate on an idea, tinker with it.”

The recent surge in people taking up skateboarding, especially during the pandemic, means there are lots of beginners in need of spaces to learn. I was curious how Sam, Esther and their colleagues at Betongpark would ensure that different abilities were catered for. Would there be different dots for different abilities, or would each dot cater to beginners and more experienced skaters? Sam described how one of the most interesting things he learned from the CMS pilot research was that lots of skateparks are quite masculine in terms of the dimensions of the obstacles. “The ledges are too high, the quarter pipes might be too high… It assumes a minimum level of ability, which for younger people, for some of the female skaters we have spoken with, it’s difficult to… get past that entry barrier in a skatepark, to be able to start having fun with it.” Many of the women Sam and Esther spoke to in the focus groups started skating later in life – in their 20s rather than as teenagers – and have a different sense of danger. “Adult beginners have to also go to work, so can’t take the same kind of risks,” explained Esther, who herself started skating at 47. Sam explained how ideally each dot would allow for progression: “It could be as easy to skate… as a curb, but it could be much more challenging… and ideally it could be both within a single obstacle.” He used the analogy of a ledge on a hill: you can skate the low section as a beginner, then take it higher as you progress. Esther agreed that scale was important, but also highlighted an issue relating to the placement of obstacles that emerged from the group’s conversations with adaptive skateboarders: if you are in a wheelchair, you don’t want to have to have somebody there to push you back up the hill so that you can ride again. “It’s easy to avoid that, it’s just that previously in skatepark design, that hasn’t been a factor that’s been thought about,” Esther added.

I asked Sam and Esther how the models will be used in the design and construction of the dots, specifically if a number of models would be chosen and realised, or if some of the favourite elements Sam described above would be cherry-picked and combined. Sam was keen to explain that the aim was to re-express the ideas as best they could, but that some caveats were attached. The dots that are built will have to function in the context of the sites in which they are placed and that will inform the process in terms of which ones end up where, he explained. Sam went on to describe a test stage, where: “initial dots are created in… a slightly more DIY way… they are actually subjected to practical testing.” This iterative process of testing and learning and trial and error is in the spirit of skateboarding itself, Sam added. The test stage would, according to Esther, help when they have to go back to UCL and say: “Right, this is what we want to make. This is what our focus group have told us, this is how it can integrate into the landscape / architecture, so we will need this much money / time / space.” CMS has the money to build to test skate dots but due to lockdown, the UCL meanwhile spaces are not yet available and they have not yet found a suitable space to build. “The Hackney Bridge site is one of the possible locations we have explored,” added Esther.

Skatepark designers and builders Betongpark are working with Sam and Esther on City Mill Skate. Recent Betongpark projects include Cann Hall and unofficially, the Hackney Bumps renovations during the pandemic. I asked Sam and Esther how Betongpark fits into what must be for them, an unusual project. Sam explained that Daryl and his colleagues represent a useful balance between having a very detailed knowledge of planning and not wanting to do cookie-cutter stuff. They approach skatepark design like landscape architecture in the sense that they are interested in expressing local history or local bits of culture, which is perfect for creating punctuations as part of a wider, holistically considered landscape, explained Sam. Esther added that from her first meeting with Daryl, it was obvious that he relished, not just accommodated, the participatory aspect of the project: “It was like that spoke to the essence of Betong and I think that sense of them being really quite intrinsically connected to a DIY ethos of being something that grows out of the activity that’s going on there.”

With London’s skateboarders and non-skateboarding members of the public not used to the types of mixed-use public spaces common in Malmö and Copenhagen, I was curious how Sam and Esther saw contestations for use of the dots playing out. For example, what would happen if some skaters showed up to skate their chosen dot and a family was picnicking on the obstacles? Sam sees this as a natural extension of the etiquettes that already exist in skateboarding: “Skaters have to learn those tacit rules through street skating anyway. If you go and skate an underground car park in the winter, you don’t leave it full of garbage.” Furthermore, there are often obstacles out of your control when you go street skating: “You could show up to a great street spot that’s got a car parked in front of it. You can’t always control it,” Sam added. Esther is optimistic about skateboarders’ ability to be decent human beings: “Perhaps I’m naïve but I’ve seen a lot of evidence to support that opinion. Even at the Bumps, the big quarter is for skating, but quite often there are kids climbing up it… which is a pain for everybody who wants to skate it, but I think mostly people are gently suggesting that the kids go somewhere else. I don’t see people wading in…”

Sam went on to explain how the scenario of the picnicking family is absolutely and fundamentally critical to the idea of the skate dot. Where you have a series of punctuations in the landscape, if somebody is sat on one, in theory it shouldn’t be a problem, because there are others nearby. “That in a sense is how street skating sometimes works. It’s a roll of the dice but it doesn’t matter because there’s something around the corner. You know, you can come back to it later,” said Sam. Esther added that seating around the dots for people to watch skateboarding is being considered, which would further mitigate these potential conflicts. To conclude I asked if Sam and Esther thought CMS would inspire similar projects elsewhere in London and around the country and perhaps change the attitude to mixed-use spaces in the UK, specifically provision for skateboarding in public spaces. I mentioned the standard response to street skating from members of the public here: “Didn’t you know there is a skatepark down the road?” and suggested that the non-skateboarding public may, generally speaking, be more enlightened in cities like Malmö and Copenhagen, which have pioneered such spaces (Värnhem in Malmö for example). Sam hopes so: “City Mill Skate could become a useful case study for people to refer to moving forward about the need for skateable spaces and public spaces to not be mutually exclusive, that it’s totally fine and in fact it’s entirely necessary to place the decision making around what skateable obstacles can look like in the hands of skateboarders themselves with guidance and custodianship around that.” However both Sam and Esther were quick to point out that CMS should not be used a definitive methodology that can be applied anywhere. According to Sam, any successes of CMS so far result from them paying very close attention to the local context and tailoring what they are doing around that. Esther went further, highlighting the importance of listening to local people: “It can’t be a how-to guide, because what we’d say in terms of how to do something like this is listen. Listen to your community. Listen to your audience and they’re going to say different things than our group did.”

You can watch City Mill Skate Dots and Lockdown here. Find out more about the project here. Enjoy lots more skate dots below.